Utilizing Clinical Observations to Specify the Course of Bipolar Disorder

A major challenge is the highly heterogeneous clinical presentation and phenomenology of bipolar disorder, with intra- and inter-individual differences in the severity of mania (bipolar type I vs. bipolar type II), presence vs. absence of mixed features or anxious distress, early vs. late onset, rapid cycling, presence vs. absence of psychotic symptoms (Figure 1). In addition to this, psychiatric and physical comorbidities are the rule rather than the exception, with up to 90% of patients meeting criteria for one or more comorbid conditions.4

Particularly prevalent comorbid conditions include substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, migraine, and cardiovascular diseases, with differential patterns of comorbidities being associated with a more complex illness presentation, greater illness severity, and a worse long-term outcome, including increased suicidality and self-harm, and suboptimal response to treatment.4 This marked clinical heterogeneity results in apparent sub-phenotypes that exhibit distinct courses of illness, prognoses, and treatment response. Hence, intra- and inter-individual clinical heterogeneity in bipolar disorder not only complicates the initial diagnosis but also poses challenges in determining optimal treatment strategies.

Intra- and inter-individual clinical heterogeneity in bipolar disorder not only complicates the initial diagnosis but also poses challenges in determining optimal treatment strategies.

Figure 1: The Clinical Heterogeneity in Bipolar Disorder within Several Domains

Bipolar disorder is associated with marked clinical and phenotypic heterogeneity, including differences in symptomatology, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and neurocognitive function. Intra- and inter-individual differences increase the complexity of the disorder, which complicates accurate diagnosis, management, and understanding of the underlying mechanisms of bipolar disorder.4,32

Among the most consistent clinical predictors of the course of bipolar disorder is the age of illness onset. Bipolar disorder typically manifests in late adolescence or early adulthood, with a majority of patients experiencing clinical symptoms before the age of 25.5

Age of illness onset is clinically relevant, as it influences clinical presentation, pattern of comorbidity, illness trajectory, and response to treatment. Specifically, early illness onset is associated with a greater frequency of familial history of bipolar disorder, higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, episode recurrence, time spent with symptoms, suicide attempts, and lower levels of treatment response.6,7 However, the exact age of onset is difficult to determine – particularly in patients with bipolar type II disorder- as hypomanic episodes are not always clinically recognized. Consequently, bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed and the average delay between onset of symptoms and diagnosis is 5–10 years.8

The exact age of onset is difficult to determine – particularly in patients with bipolar type II disorder- as hypomanic episodes are not always clinically recognized. Consequently, bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed and the average delay between onset of symptoms and diagnosis is 5–10 years.8

The time to diagnosis is longer in patients who exhibit a more complex illness presentation, with higher rates of comorbidities and depressive onset.7 Importantly, this duration of untreated illness – representing the time from the initial episode to appropriate management – drives prognosis, with longer duration of untreated illness being associated with longer duration of illness and an increased number of suicide attempts.9

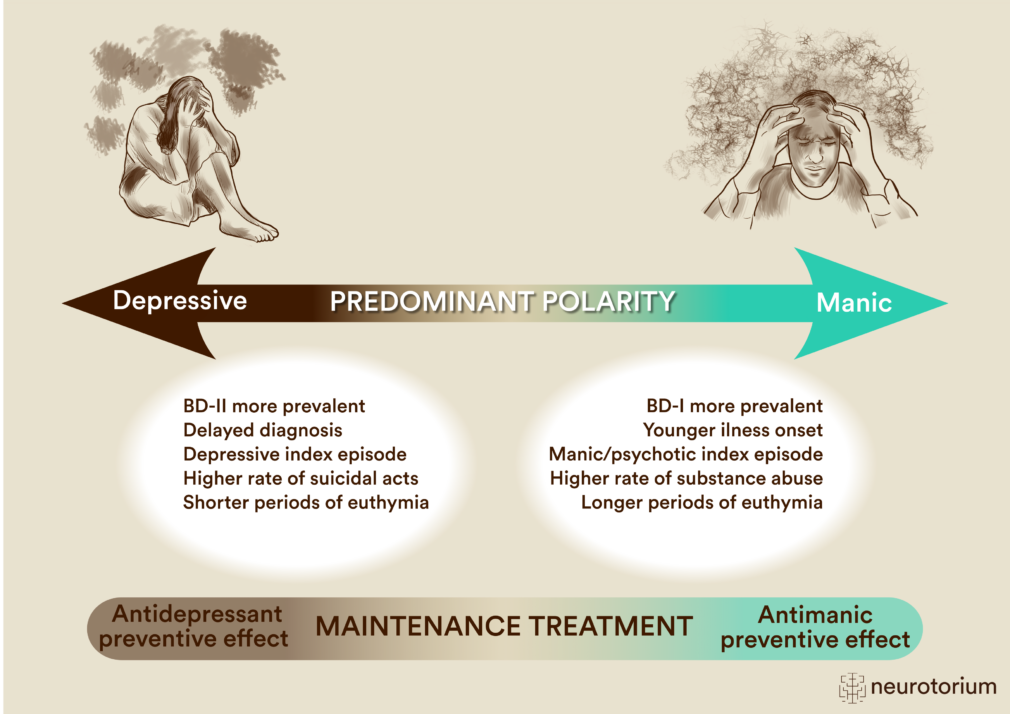

Another clinically relevant course specifier in bipolar disorder is the predominant polarity of mood episodes. This concept refers to the pole at which a patient experiences at least twice as many episodes compared to the other pole. Predominant polarity is, however, not observed in all patients. Evidence suggests that predominant polarity has prognostic value and clinical and therapeutic implications.10

Evidence suggests that predominant polarity has prognostic value and clinical and therapeutic implications.10

Depressive predominant polarity has been associated with a greater delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorder, depressive index episode, bipolar disorder type II, higher rates of suicidal acts, and shorter duration of euthymia. Manic predominant polarity has been associated with earlier illness onset, manic/psychotic index episode, greater prevalence of comorbid substance abuse, and longer duration of euthymia (Figure 2).11,12 Indeed, understanding the patient’s predominant polarity can be important in the management and treatment of bipolar disorder, as it can guide treatment selection. As such, it has been proposed that pharmacological maintenance treatment should be tailored to the individual patient’s predominant polarity.2 The polarity index serves as a metric for classifying maintenance therapies, distinguishing between those with a predominant antidepressant prophylactic profile and those with an antimanic prophylactic profile (Figure 2). Accordingly, individuals with a depressive predominant polarity, often seen in bipolar type II, may exhibit a more favorable response to treatment with lamotrigine and could be more likely to require adjunctive antidepressant therapy. In contrast, individuals with a manic predominant polarity, often seen in bipolar type I disorder, may respond better to atypical antipsychotics or lithium, and antidepressant cotreatment may be better avoided.2,10,13

Figure 2: Predominant Polarity in Bipolar Disorder

Predominant polarity in bipolar disorder (BD) refers to the dominance of either depressive or manic episodes in an individual’s illness history. Depressive predominant polarity is typically defined as having at least two-thirds of lifetime episodes being depressive, whereas manic predominant polarity refers to at least two-thirds of prior episodes being (hypo)manic episodes. Studies show that predominant polarity has prognostic value and clinical and therapeutic implications. Clinical correlates of depressive predominant polarity include greater delayed diagnosis, depressive index episode, bipolar disorder type II, higher rates of suicidal acts, and shorter duration of euthymia. Clinical correlates of manic predominant polarity include earlier illness onset, manic/psychotic index episode, greater prevalence of comorbid substance abuse, and longer duration of euthymia.11,12 The polarity index classifies pharmacological treatments as those with an antimanic prophylactic effect and those with an antidepressant prophylactic effect. For further information on this topic, please go to Vieta et al. 2018.2

Cognitive Dysfunction in Bipolar Disorder

Many patients with bipolar disorder display persistent cognitive impairments despite reaching clinical remission, which are associated with poorer quality of life and everyday functioning – such as the ability to work and participate in work-related activities and social relationships – poorer prognosis, lower treatment adherence, and response.14-17 Cognitive impairments in bipolar disorder comprise moderate neurocognitive deficits within non-emotional domains, including attention, verbal learning and memory, and executive function,18 as well as impairments in socio-emotional cognition, including measures of facial expression recognition, theory of mind, and emotion regulation.19

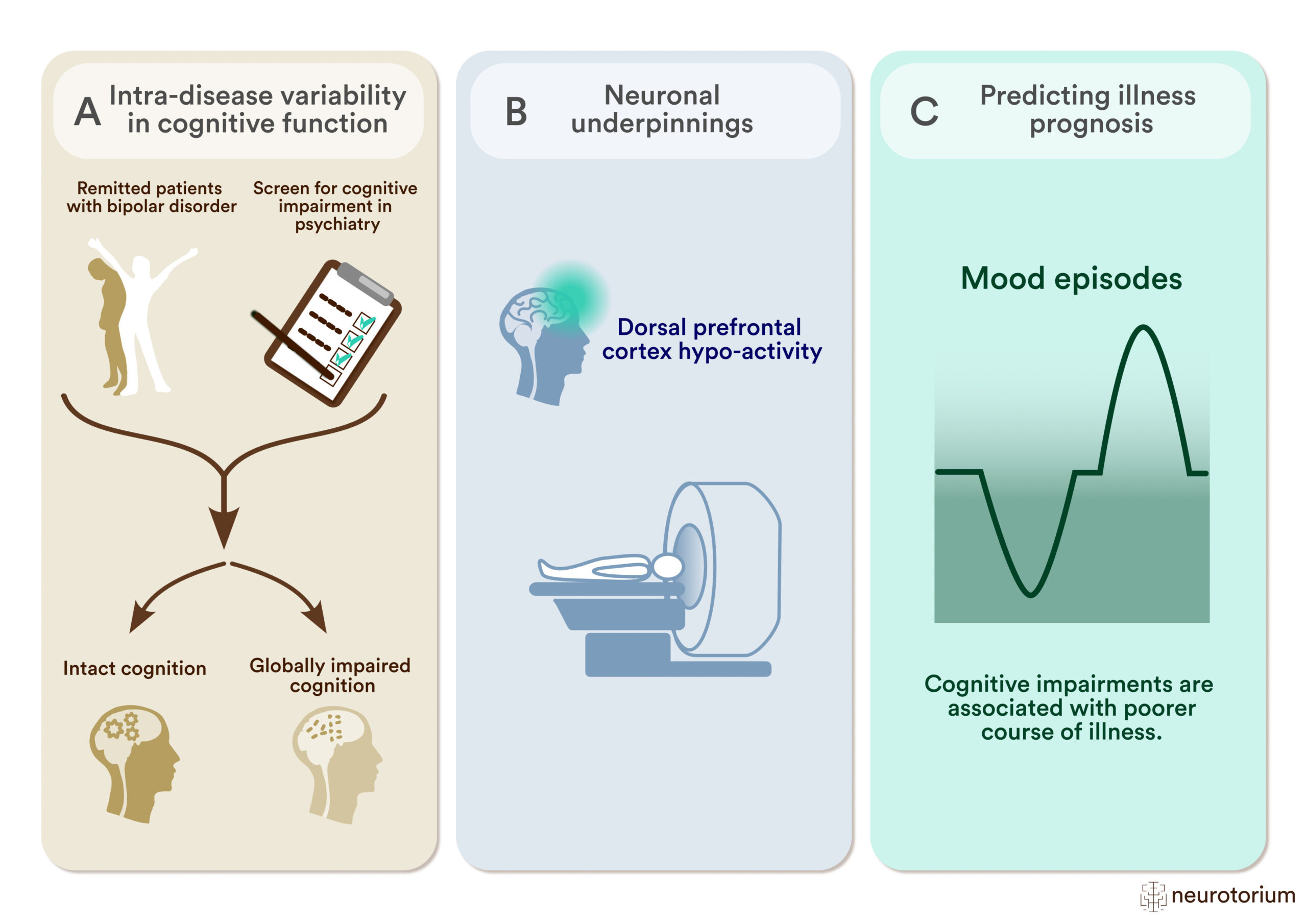

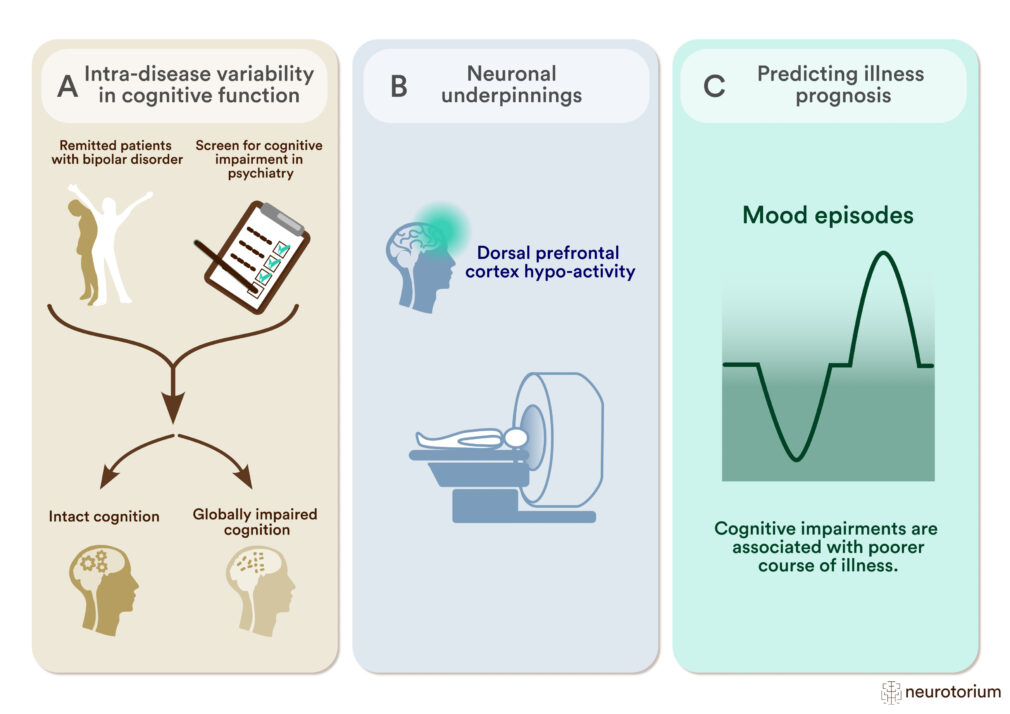

Despite these well-documented impairments at a group-level, patients with bipolar disorder exhibit substantial cognitive heterogeneity. Recent data-driven studies show patient subgroups with distinct profiles of non-emotional and emotional cognitive functions, where approximately 30-50% present with broad, global impairments, and 50-70% are cognitively intact.20-23 Notably, these impairments seem to persist over time and are associated with a more adverse subsequent illness course in globally impaired subgroups, including heightened risk of relapse, psychosis, more frequent hospitalizations, and lack of improvement in functioning (Figure 3).21,24-26 Cognitive heterogeneity may therefore map onto distinct clinical trajectories and be useful for prediction and reflecting potential treatment targets.

Cognitive heterogeneity may therefore map onto distinct clinical trajectories and be useful for prediction and reflecting potential treatment targets.

Additionally, non-emotional and emotional cognitive impairments are accompanied by structural and functional neuronal underpinnings. Specifically, remitted patients with cognitive impairments demonstrate greater gray matter thickness in the left dorsal prefrontal cortex (dPFC),27 along with dPFC hypo-activity during both working memory28 and emotion regulation26 fMRI tasks measuring BOLD activity. Global cognitive impairments in a subgroup of patients with bipolar disorder may thus originate from insufficient recruitment of dPFC resources, indicating that modulation of aberrant dPFC activity could serve as a marker for indicated pro-cognitive treatment.

Figure 3: Studying Cognitive Impairment and its Neuronal Underpinnings to Predict Illness Prognosis in Bipolar Disorder

A) To study intra-disease variability in cognitive function, researchers employ data-driven clustering methods to differentiate patients with widespread cognitive abnormalities from patients who are cognitively intact.

(B) Comparing the patient subgroups in working memory-related neural activity during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) shows hypo-activity within the dorsal prefrontal cortex (dPFC) in cognitively impaired patients.28

(C) Cognitive impairment and associated neuronal abnormalities correlate with features of poorer illness course (mood episodes, hospitalizations) and help to predict illness prognosis.16,24,26

Taken together, there is a clear need for implementing systematic cognitive assessment and screening in the clinical management of bipolar disorder. Specifically, the International Society of Bipolar Disorder Targeting Cognition Task Force29 recommends the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP)30 and the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment (COBRA).31

The SCIP is a brief 10–15-minute measure of objective cognitive impairments within the domains of verbal learning and memory, verbal working memory, verbal fluency, and psychomotor speed.30 The COBRA is a 16-item self-report questionnaire (<5 minutes) assessing subjective cognitive difficulties in daily life scenarios.31 It is important to highlight that these cognitive assessments do not substitute a comprehensive neuropsychological battery but are brief and feasible to implement in clinical practice. The implementation of brief cognitive screening tools, such as the SCIP, in clinical settings for symptomatically stable patients with bipolar disorder can help identify patients with cognitive impairments who are at a higher risk of disease recurrence and progression.

The implementation of brief cognitive screening tools, such as the SCIP, in clinical settings for symptomatically stable patients with bipolar disorder can help identify patients with cognitive impairments who are at a higher risk of disease recurrence and progression.

Characterizing specific cognitive subgroup profiles and their trajectory can inform a personalized approach to treatment. These patients would benefit from psychoeducation cognitive strategies and interventions targeting specific non-emotional and/or emotional cognitive impairments. This targeted approach may mitigate the risk of adverse illness courses, such as future relapse and psychiatric hospitalizations, and directly improve patients’ functional capacity and quality of life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the multifaceted clinical landscape of bipolar disorder, marked by its heterogeneous presentation and the prevalence of comorbidities, underscores the challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Age of onset, predominant polarity, and cognitive impairment emerge as pivotal clinically accessible predictors, influencing not only the clinical trajectory but also treatment response. Overall, addressing the clinical intricacies and cognitive dimensions of bipolar disorder is crucial for enhancing patient outcomes and advancing the field of bipolar disorder research and management.

Age of onset, predominant polarity, and cognitive impairment emerge as pivotal clinically accessible predictors, influencing not only the clinical trajectory but also treatment response.