Since sleep regulation involves many neurotransmitter systems and brain circuits, it is likely that the mechanisms generating normal sleep overlap with those that maintain mental health. This would explain why disturbed sleep and schizophrenia are so intimately linked. This was the essence of a seminar given on 17th April 2015 by Russell Foster, director of the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Unit at the University of Oxford, UK.

Sleep disturbance is common in serious mental illness, and schizophrenia is no exception. It is widely accepted that schizophrenia disrupts sleep and circadian rhythms. But it also seems that disturbances of sleep can precede severe mental illness and may even help cause it.1

Sleep problems: Common and important in psychosis1

- Sleep is less regular, may occur at any time of the day or night, and may be too much or too little.

- It can be hard to get sleep or stay asleep.

- Symptoms of fear or anxiety often affect sleep.

- A change in sleep may precede onset of psychosis or relapse.

- Sleep problems cause other major health problems – both physical and mental.

Sleep and circadian abnormalities

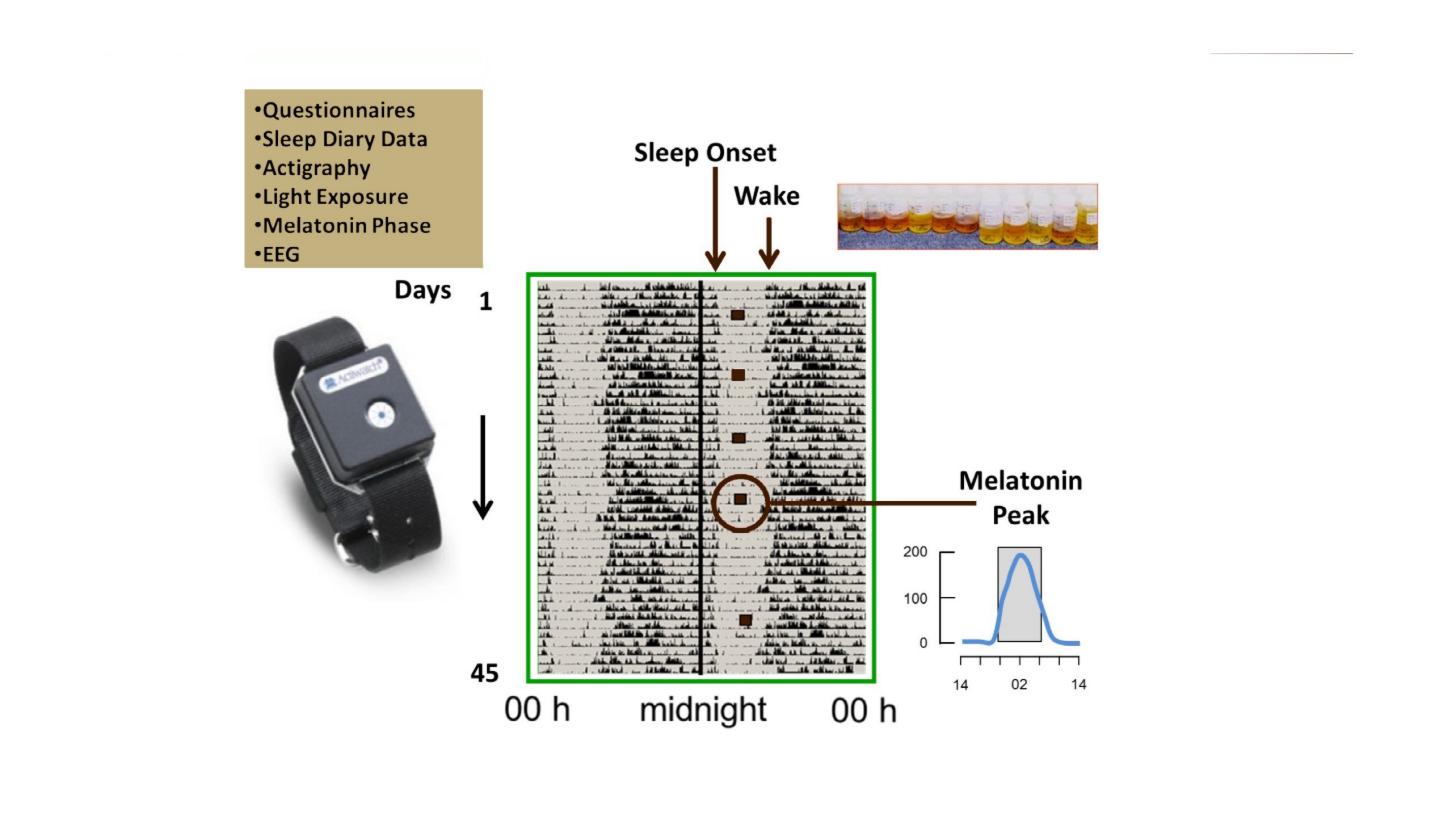

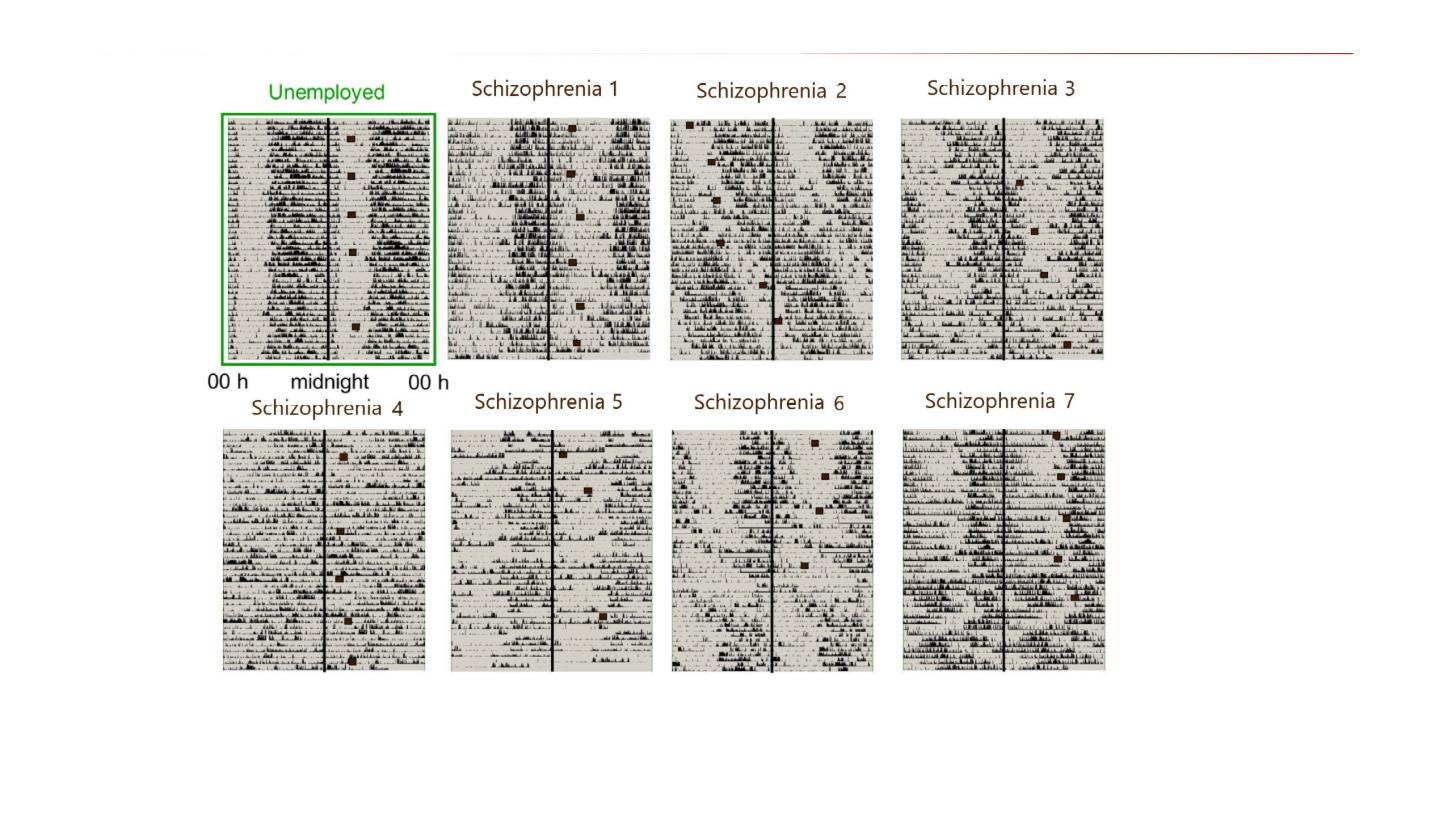

In a landmark study, Foster and colleagues compared the sleep-wake activity and circadian rhythms of 20 outpatients with schizophrenia (median duration of illness ten years) and 21 healthy controls over a period of six weeks.2 No patients and no controls were in paid employment.

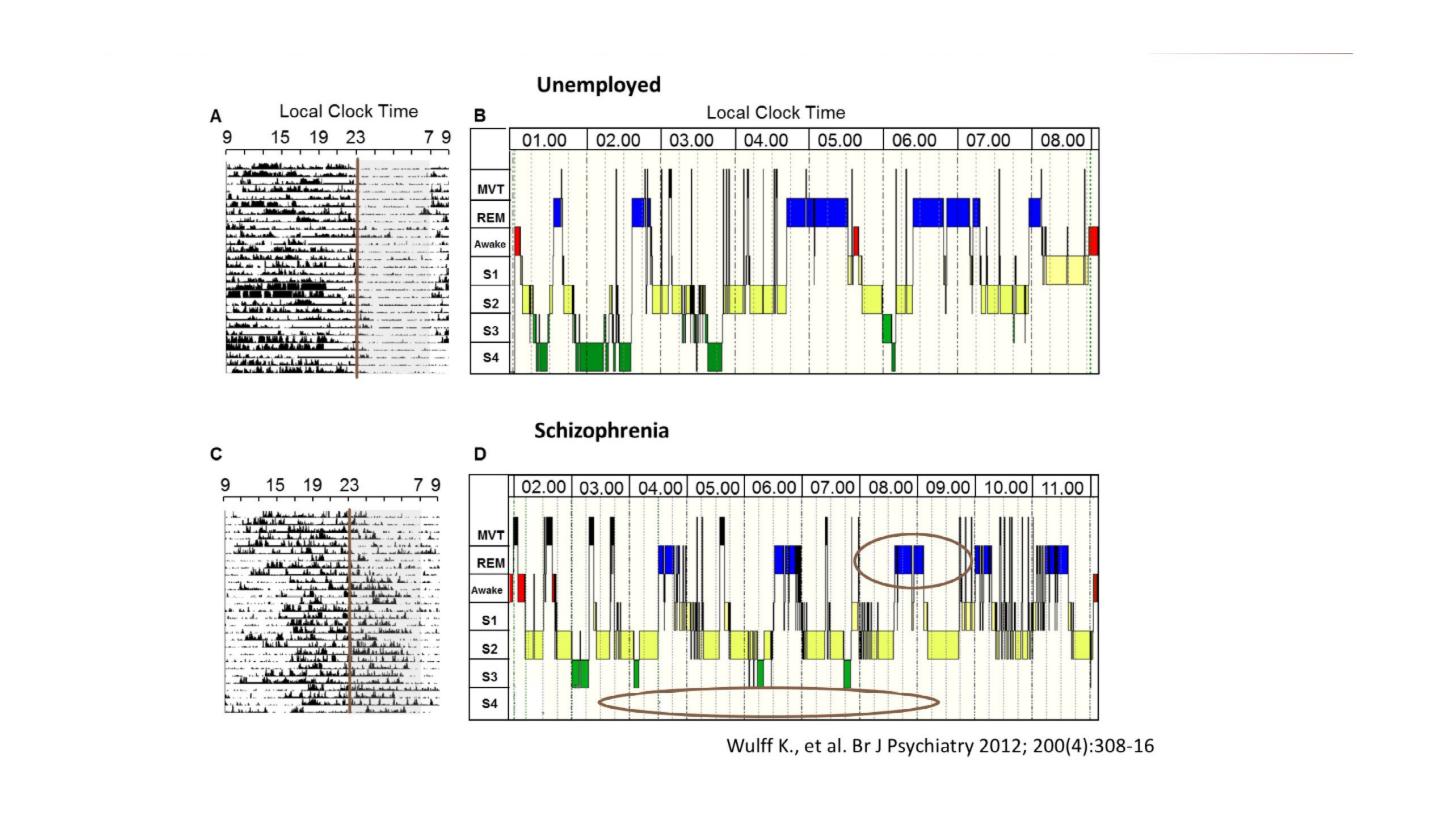

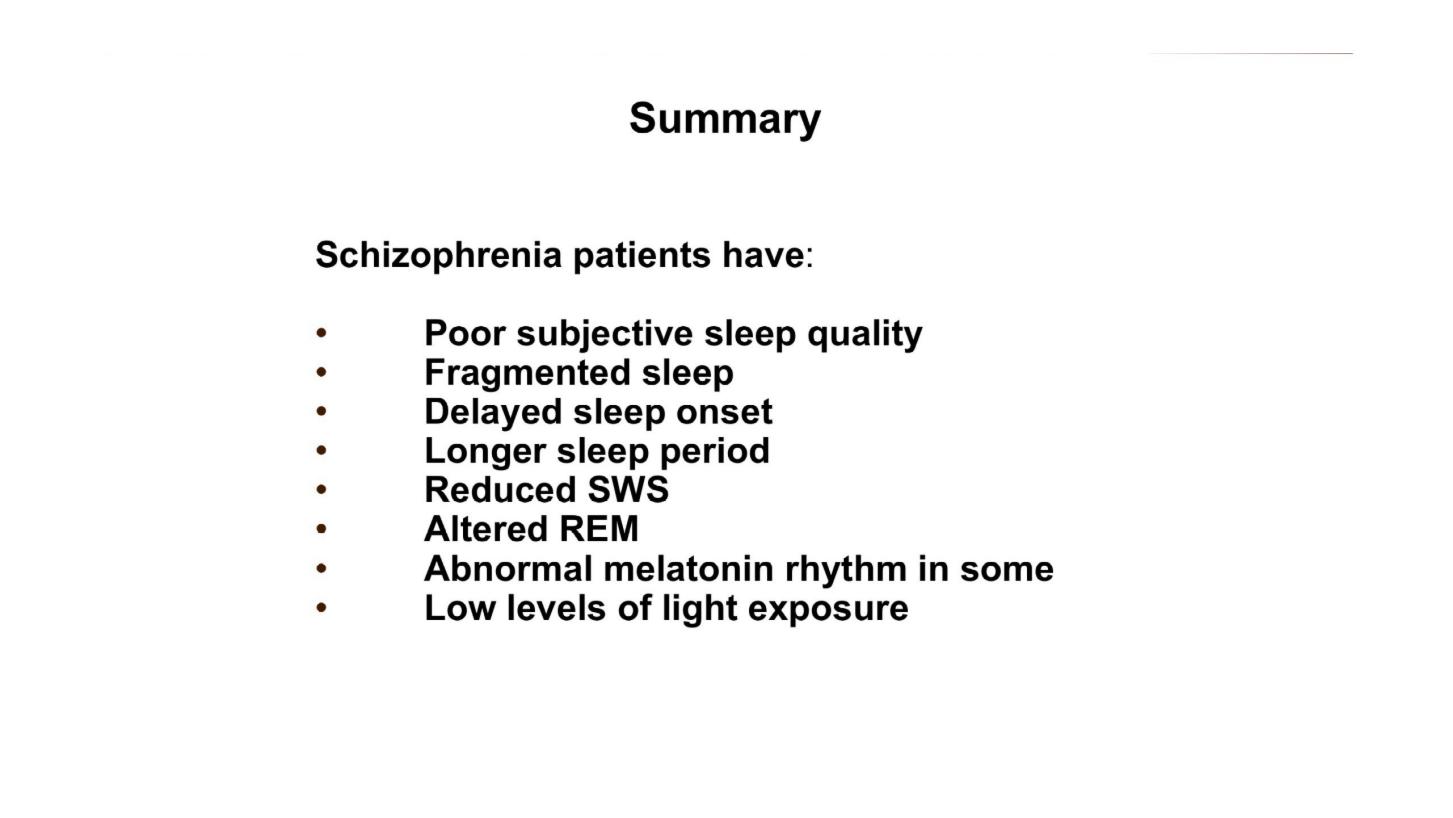

Despite the fact that patients were on newer antipsychotic medication and their symptoms relatively well controlled, sleep was of significantly poorer quality in patients than in controls, and more fragmented. On average patients with schizophrenia took 15 minutes more to fall asleep and slept two hours longer. Importantly for memory function, they showed less slow wave sleep than controls, and this may be relevant to poorer formation and consolidation of memory.

“Nature’s soft Nurse”

Shakespeare, in Macbeth

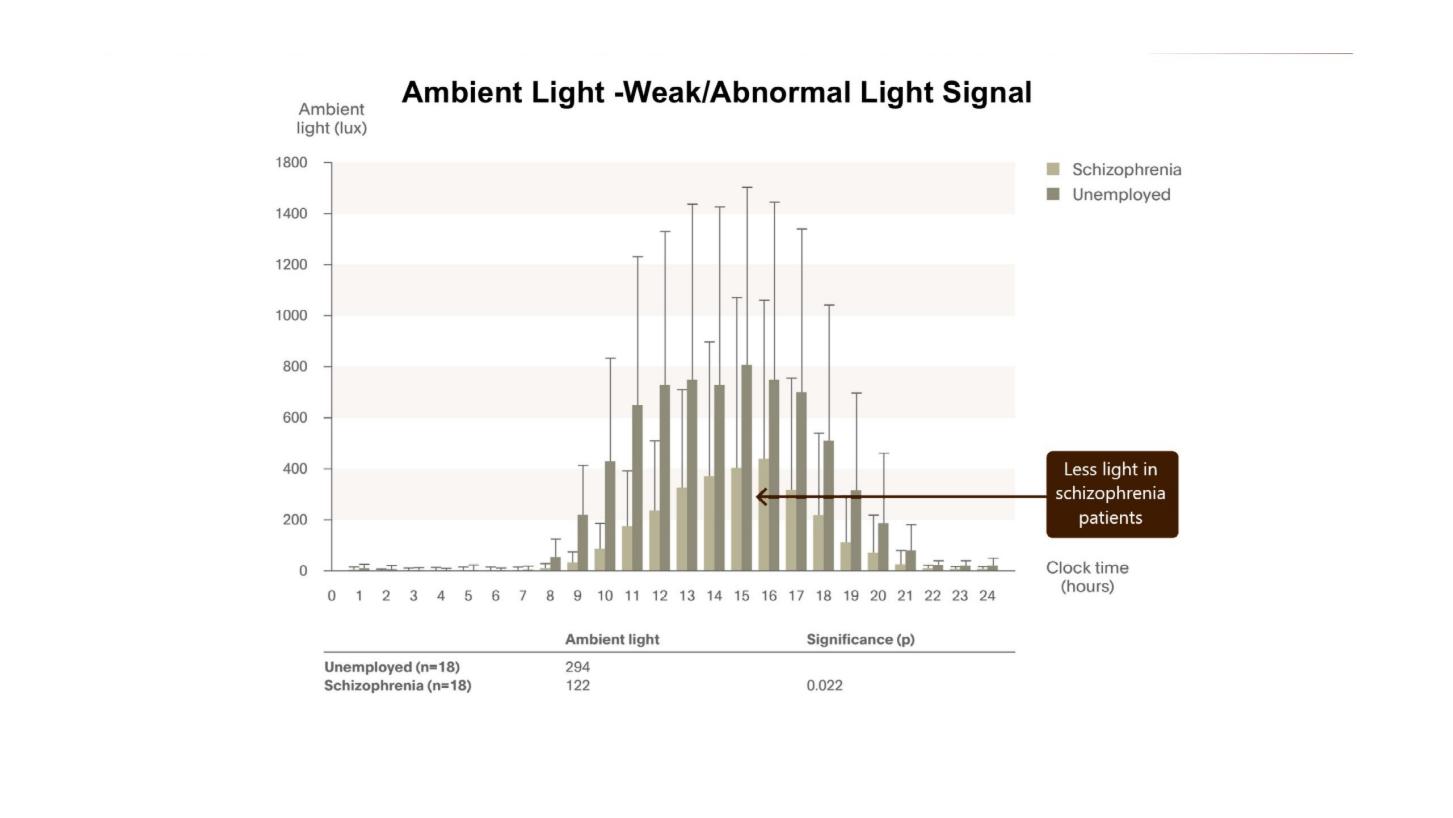

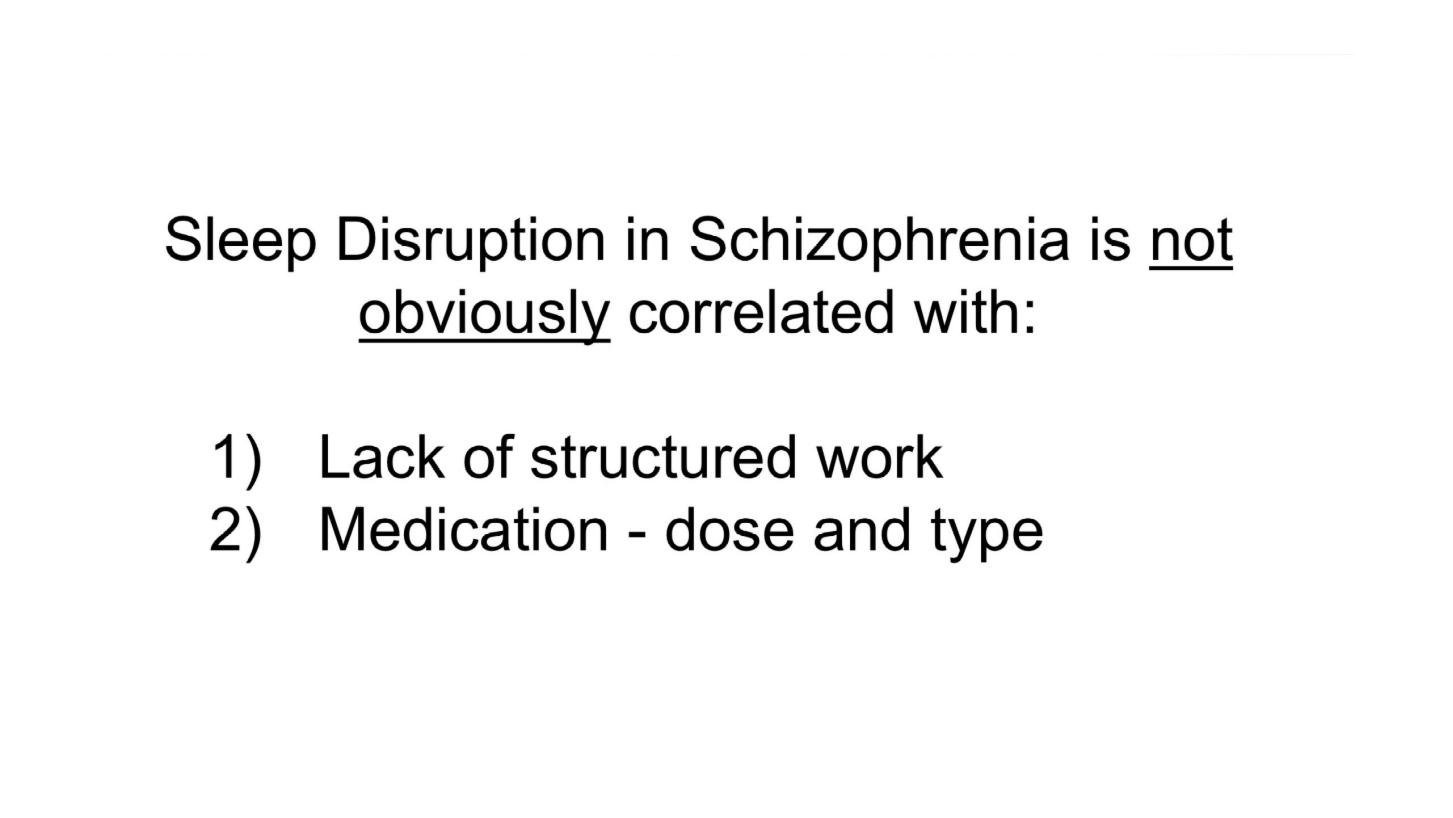

Compared with healthy subjects, patients had low levels of exposure to natural light, which may have impaired the setting of the internal clock, and the circadian melatonin rhythm in many was abnormal – suggesting lack of synchronisation between the external cycle of day and night and the body’s internal rhythm. Medication dose was not related to the extent of circadian abnormalities.

The fact that the control group was not employed suggests that lack of structured work does not account for the different sleep patterns of people with schizophrenia.

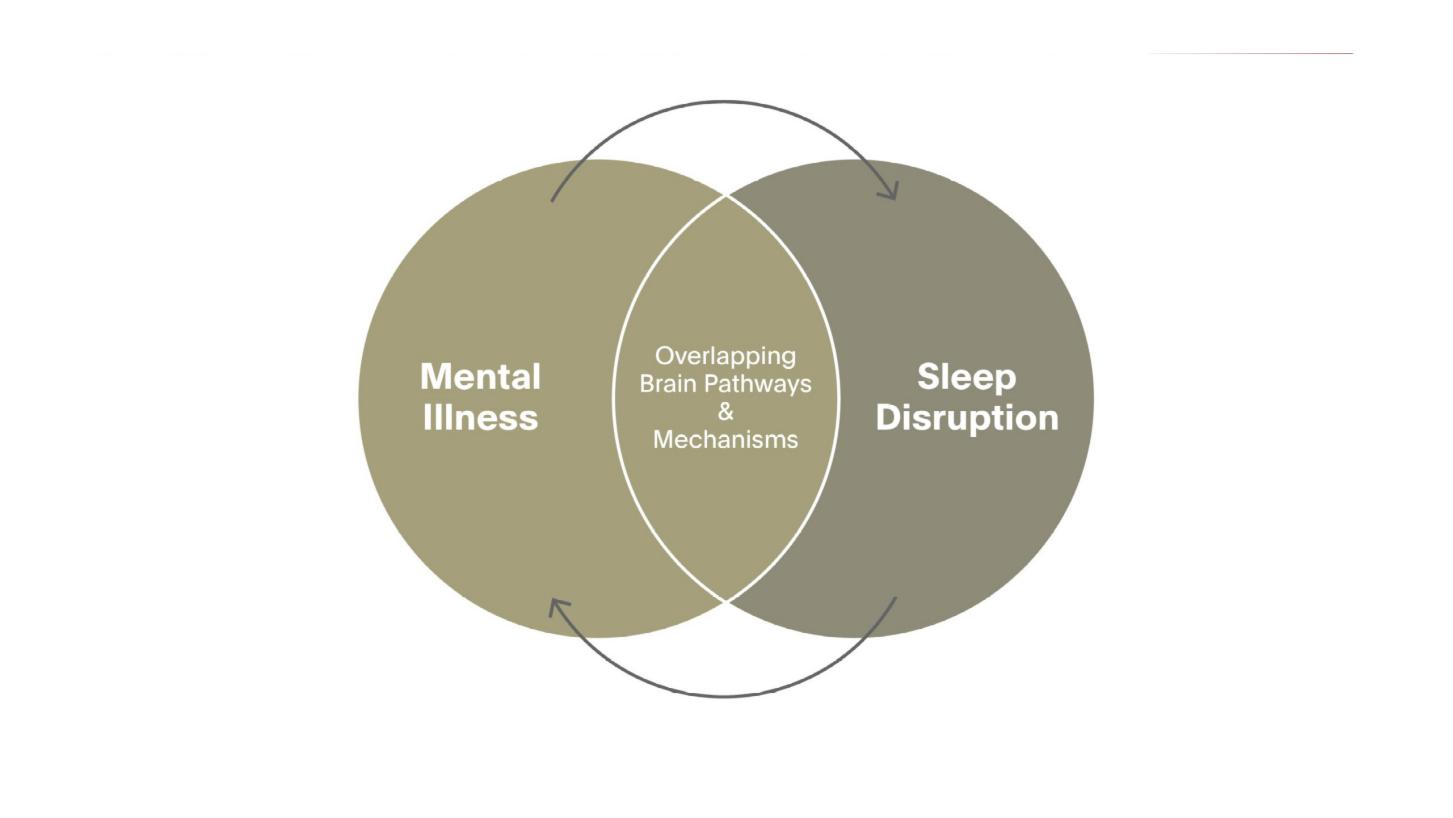

A common aetiology? – Common and overlapping brain pathways

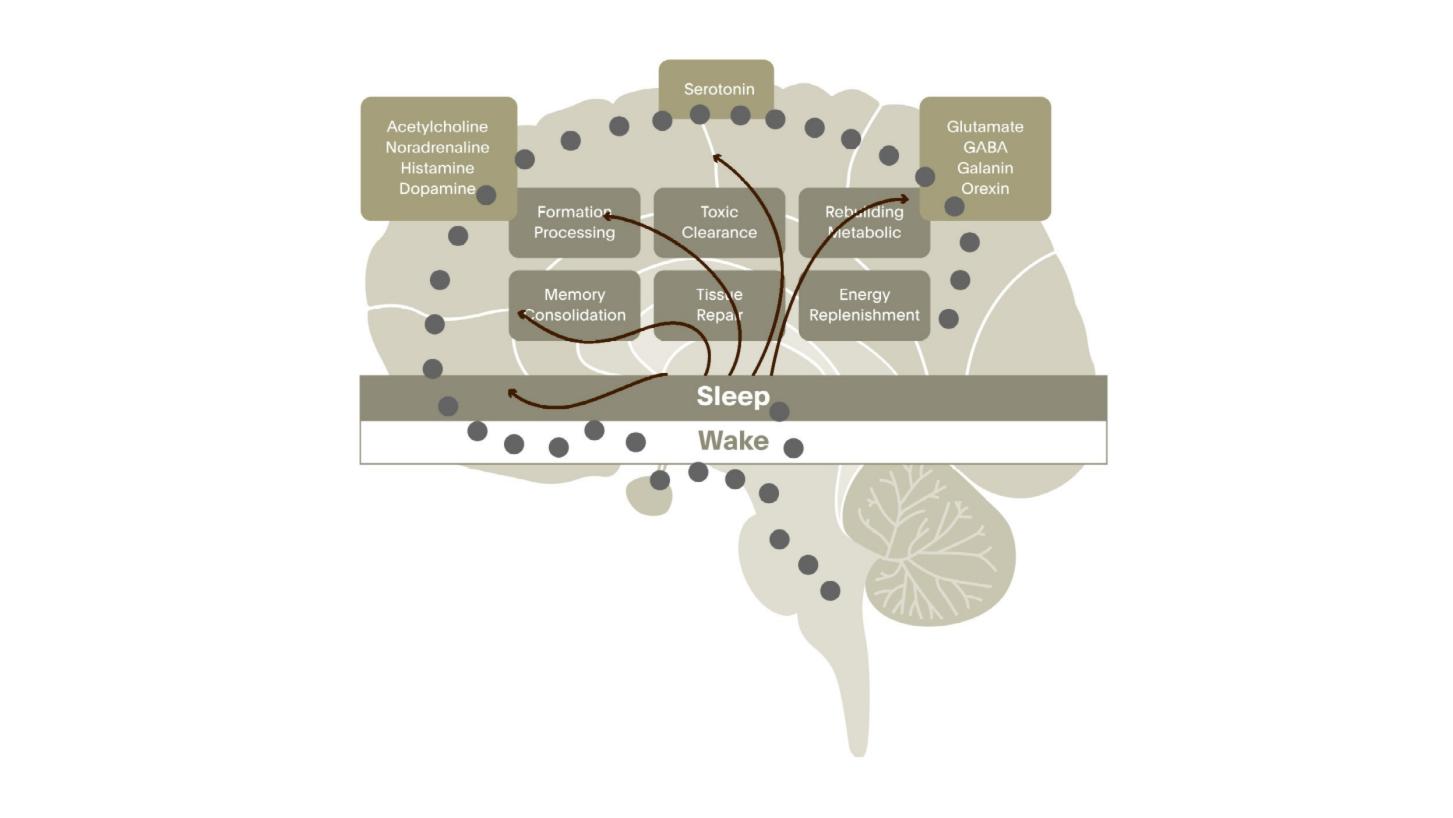

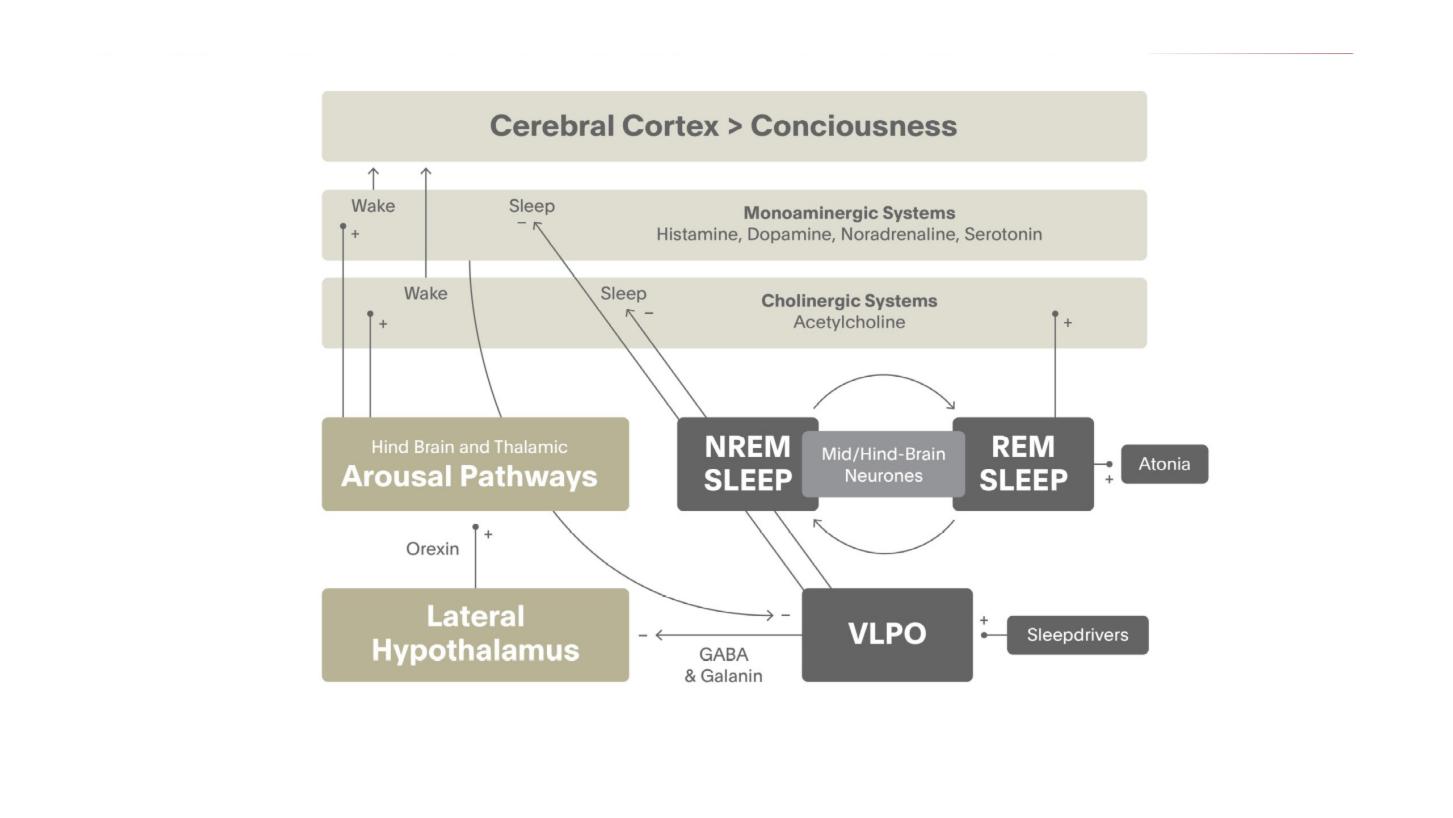

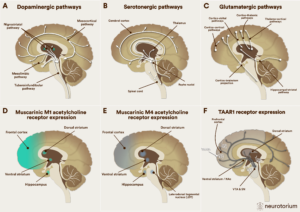

Foster and colleagues presented a new concept of understanding the relationship between psychiatric illness and sleep and circadian rhythm disruption.3 A working hypothesis is that the abnormalities in neurotransmitter signalling and regulatory pathways that predispose to mental illness also cause disruption of sleep.

A defect in neurotransmission that predisposes an individual to mental health problems may also cause some type of sleep disruption. The sleep disruption will almost certainly exacerbate – or maybe even provide the final nudge into – mental illness and the mental illness will exacerbate the sleep disruption. Prior to this, sleep disruption in psychiatric illness was essentially dismissed as an artefact of medication or social isolation.

There is early evidence that genes linked to schizophrenia in humans affect sleep and circadian rhythms in mice.4 An as yet unpublished study from the Oxford group suggests that a breakdown in the sleep/wake cycle is already evident in people at high risk of bipolar disorder who have not yet developed the disease.

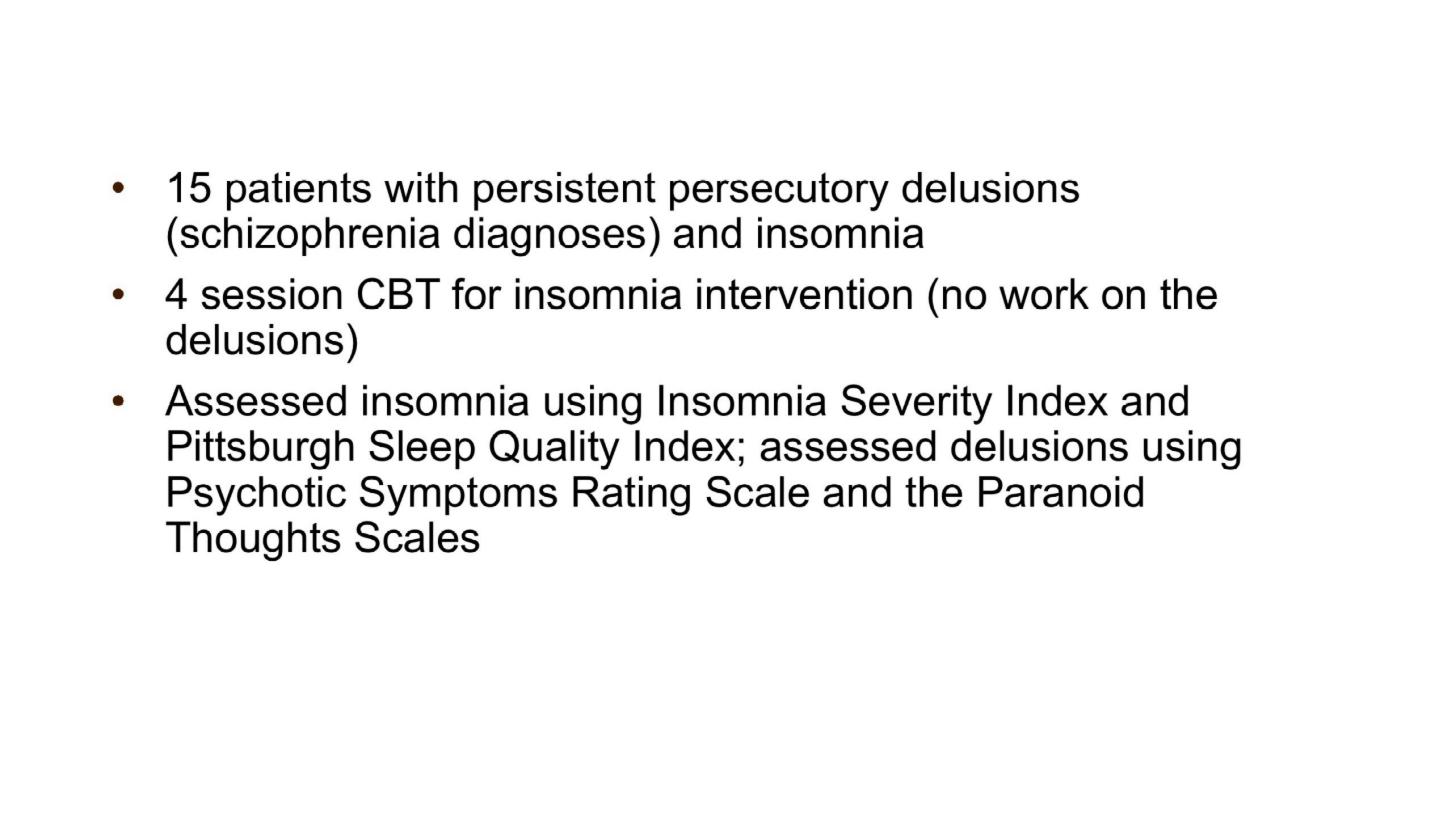

Sleep draws upon all of the neurotransmitter systems of the brain

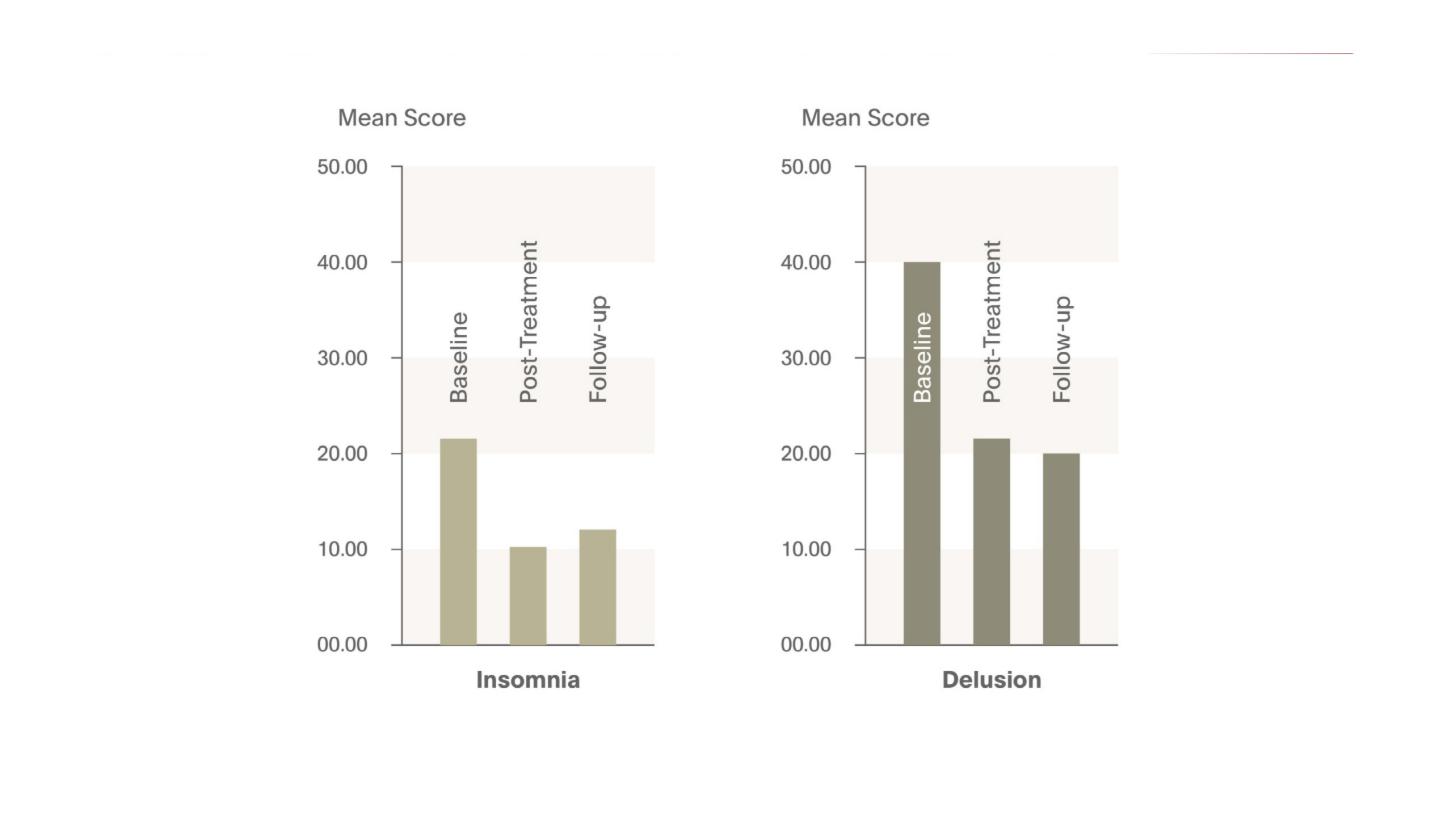

If these ideas can be substantiated, sleep would represent a new therapeutic target, both in the prevention of mental illness and its treatment. And there is evidence from a pilot study that cognitive behaviour therapy for insomnia can improve the condition of schizophrenic patients with persistent persecutory delusions.5 This study evaluated the treatment of insomnia in individuals with persecutory delusions to establish whether reducing insomnia will reduce paranoid delusions. In 15 patients who received cognitive behavioural intervention for insomnia (CBT-I) intervention, levels of insomnia and persecutory delusions were significantly reduced post-treatment and at one-month follow-up. Levels of anomalies of experience, anxiety and depression were also reduced. It was concluded that CBT-I can be used to treat insomnia in individuals with persecutory delusions and also lessens the delusions.

More broadly, we should aim to develop strategies that can help patients with schizophrenia consolidate sleep and so help improve their quality of life.

In schizophrenia, sleep….

- Timing is irregular and of poor quality

- Occurs at any time of day or night

- May be too long or too short

- Is often made difficult by fear and anxiety

And, importantly,

- A change in sleep pattern may precede psychosis

Generating the circadian rhythm

The fifty thousand cells of the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) have a 24-hour cycle. Each single component SCN neuron shows this periodicity. Indeed every cell in the body is capable of this, telling us that the oscillation is driven by a subcellular molecular process. That said, the SCN – by a signal which we don’t yet understand – coordinates all of these rhythms, acting as the conductor of the orchestra, producing a regular temporal beat according to which body cells align their biology.

The genes responsible for this 24 hour oscillation have been conserved during evolution, to the extent that they are essentially the same in drosophila, mice and humans. But there are individual differences in the clock genes between humans who are “morning people” and those who are not.

Melatonin – a biological marker of the dark

This clock is of no use whatsoever unless the internal world reflects the light-dark cycle. Ultimately, it is the eye that sets the molecular oscillation so that the internal and external world are synchronised. This is achieved not only by rods and cones but also by light-sensitive retinal ganglion cells. In the absence of eyes, the body still follows a rhythm of activation and sleep, but the cycle is longer than 24 hours. With eyes, our internal clock remains aligned at least approximately to the external world.

The eye projects not only to the master clock of the SCN but to structures in the brain associated with alertness and arousal. If the amount of light is increased, we feel more alert because the eye is linked directly to brain structures that keep us awake. The eye also projects to the pineal gland which produces melatonin at night. Melatonin is not, as commonly supposed, “the sleep hormone”. Basically it is a biological marker of the dark.

The invention of artificial light has allowed us to invade the night to some extent, disturbing natural patterns of sleeping and waking. However, electric lighting (typically 100-600 lux) is far less intense than sunlight (100,000 lux). On the other hand, the fact that we spend much of the daytime indoors means the effect of naturally intense light is much diminished. So features of modern life reduce the strength of light/dark signalling to the internal clock. And this may contribute to everyday problems of sleep disruption, as well as to those evident in people with schizophrenia whose patterns of life involve less exposure to natural light.