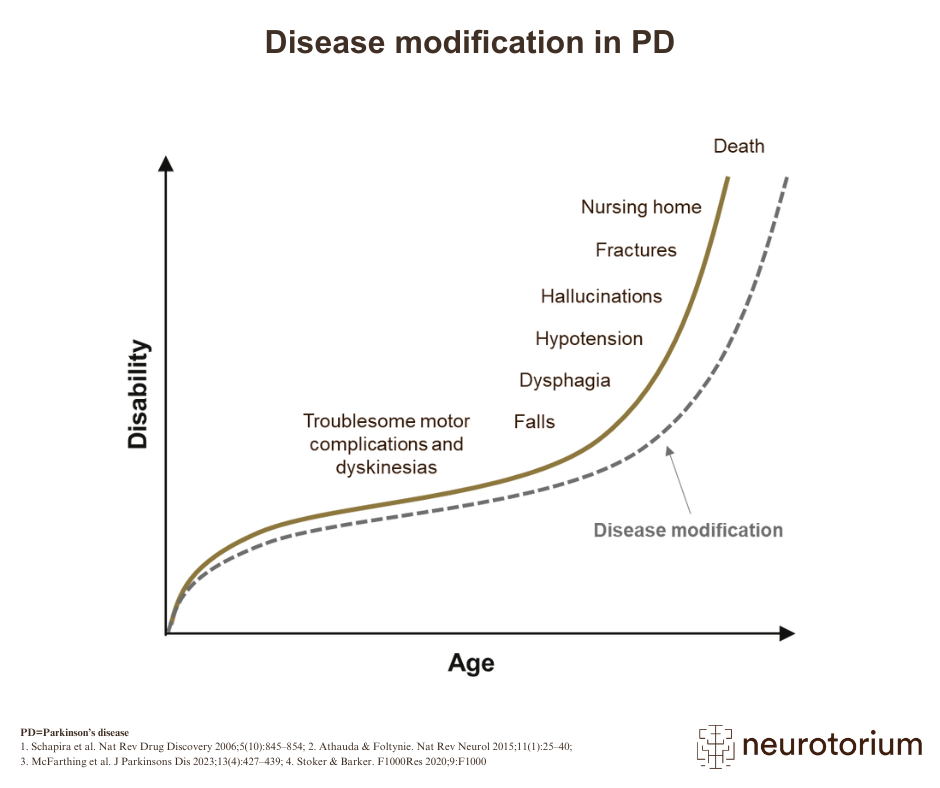

There is an unmet need for PD therapies which modify the disease course.1,2 No drug has yet been proven to be neuroprotective in PD, although several drug candidates have been tested in clinical trials.1-4 Such a strategy will only be successful if degeneration is ameliorated in multiple neurotransmitter systems, preventing the progression of both motor and non-motor features.1

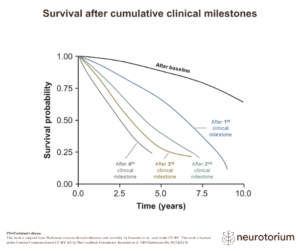

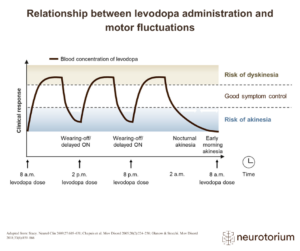

While there have been major advances in the management and reduction of PD-related symptoms, there is still no effective way of preventing or slowing the underlying neurodegeneration.2,5 As the disease becomes more extensive during its advanced stages, the ability of drugs and other coping strategies to compensate for the increasing loss of neurological function is severely reduced.2,6 Increasingly poor responses to treatment lead to a worsening quality of life for the patient, and an increased risk of PD-related morbidity and mortality.6

Many drugs have shown promise during preclinical studies as potentially protective or restorative of neurological function in PD, yet have failed during the final stages of clinical trials, and others are still being investigated in clinical research.2.4,7 Other drugs are in the pipeline but the efficacy of novel pharmacological interventions in PD can be difficult to predict.2 Potential reasons for these failures in detecting clinical benefits of potential new therapies include the lack of good biomarkers of disease state, the lack of diagnostic biomarkers for PD in general, the use of clinical rating scales that may lack the sensitivity to detect change within the timeframe of a clinical trial, an incomplete understanding of the disease process of PD, and the difference between the real-world clinical heterogeneity of the disease process of PD and that represented in clinical trials.7-9