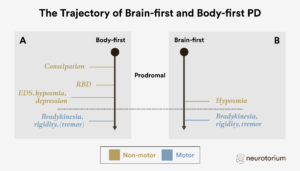

The progression of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is generally slow, taking place over years (often many years).1,2 While diagnosis tends to occur with the onset of motor symptoms, this can be preceded by a long prodromal phase of 15 years or more.1,2,3 This prodromal phase is typically characterized by a range of non-motor symptoms, including sleep disorders, hyposmia, constipation, and depression.3,4 One of the most common symptoms is ‘REM sleep behavior disorder,’ in which affected individuals can become physically, even violently, active during the REM (rapid eye movement) stage of sleep.2,3

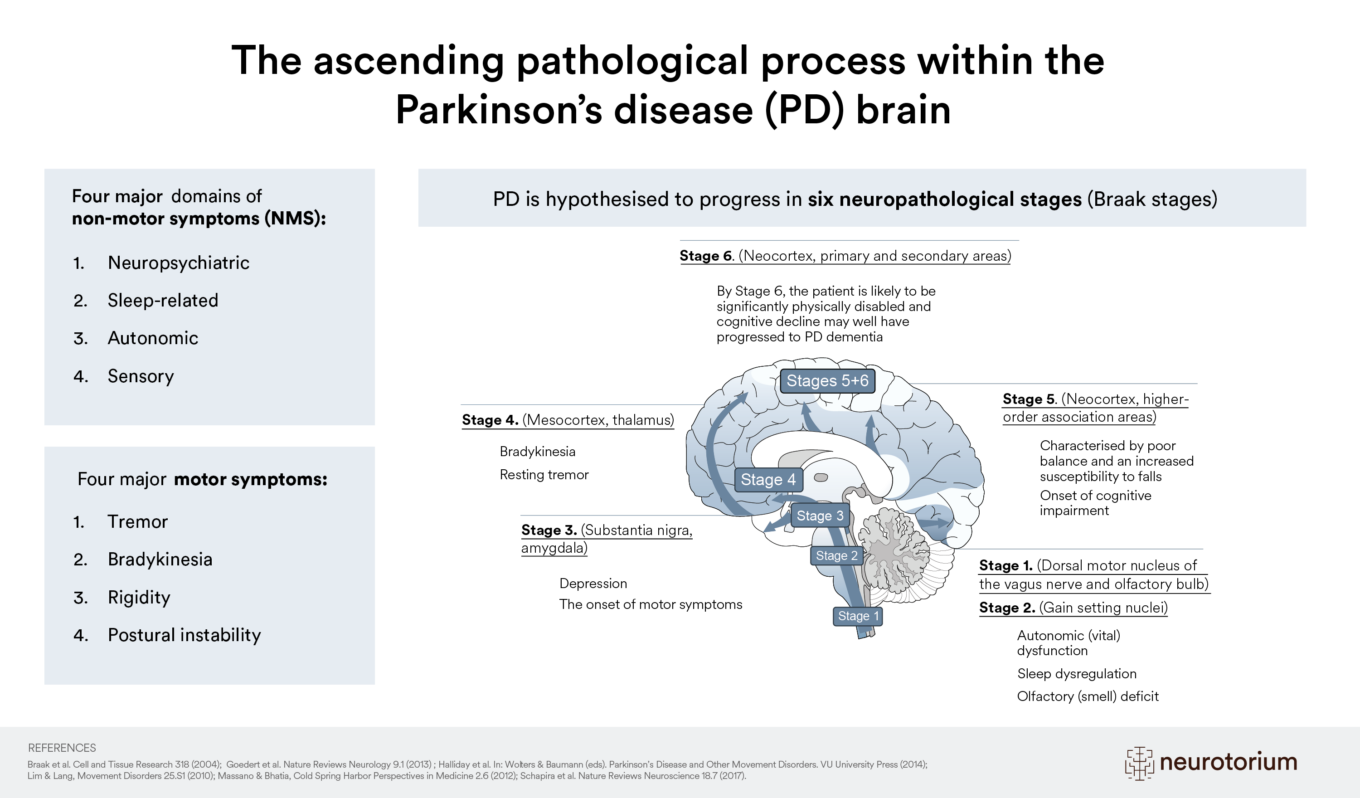

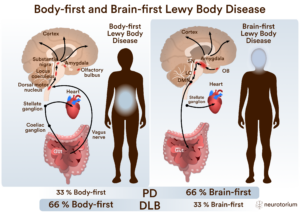

At a pathophysiological level, PD is characterized by the loss of neurons in specific regions of the brain and the spreading of Lewy pathology.5 The widely used scheme proposed by Braak and colleagues categorizes PD into stages of neuropathological changes, specifically Lewy pathology, roughly aligned with PD symptoms.6,7,8 While the Braak staging scheme is a valuable model for conceptualizing PD progression and has fundamentally changed the thinking about disease pathogenesis and its treatment6,7,9, in reality, patients vary considerably in the extent to which they conform to this model.8

Stage 1. (Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and olfactory bulb) and Stage 2. (Gain setting nuclei)

The first two stages involve early α-synuclein deposition associated with the appearance of prodromal non-motor symptoms in the domains of olfaction (smell), autonomic function (e.g., constipation), and sleep (e.g., REM sleep behavior disorder).8

Stage 3. (Substantia nigra, amygdala)

As the disease progresses, other aspects of brain function may become impaired, causing further sleep dysregulation and depression in some individuals, as well as early/prodromal motor features.8

Stage 4. (Mesocortex, thalamus)

Stage 4 is typically the point at which clinical diagnosis occurs since this stage involves the appearance of clinically apparent motor symptoms, such as resting tremor, bradykinesia, and muscle rigidity.8

Stage 5. (Neocortex, higher-order association areas)

Stage 5 is characterized by poor balance, increased susceptibility to falls, and the onset of cognitive impairment.8

Stage 6. (Neocortex, primary and secondary areas)

By Stage 6, the patient is likely to be significantly physically disabled, and cognitive decline may well have progressed to PD dementia.8