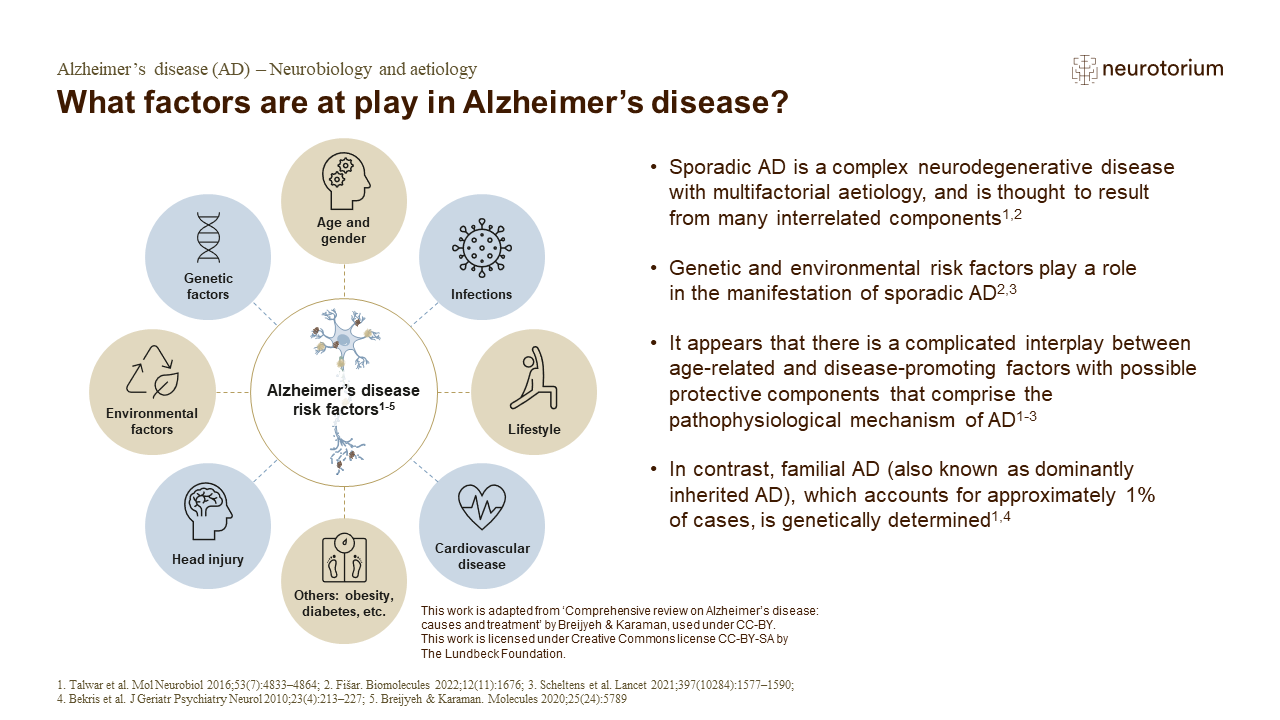

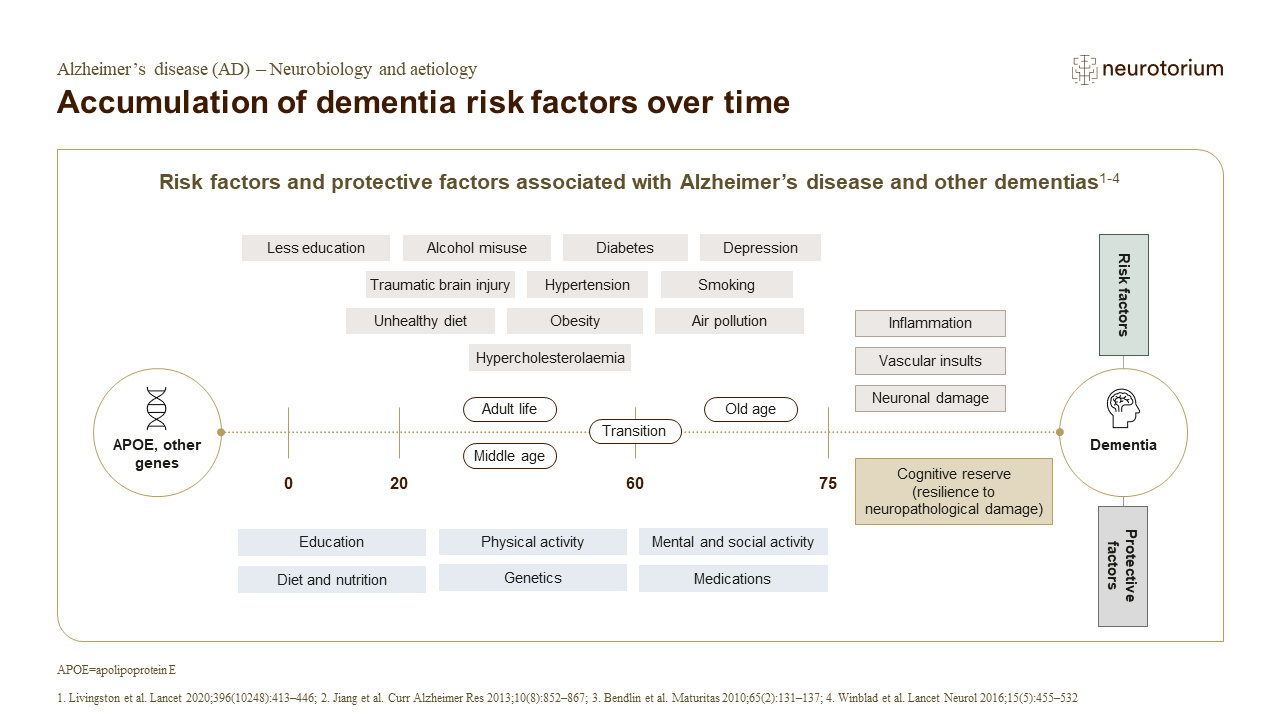

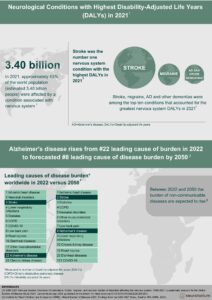

Currently, more than 55 million people are living with dementia worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates this number to double every 20 years, reaching 78 million in 2030 and 139 million in 2050. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) represents the most common form of dementia and may contribute to 60–70% of cases.1 While autosomal dominant AD (accounts for less than 1% of all AD cases) is caused by specific genetic mutations in Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), Presenilin-1 (PSEN1) and Presenilin-2 (PSEN2),2 experts believe that sporadic AD (the majority of AD cases) develops because of multiple factors rather than a single cause. The greatest risk factors for sporadic AD are older age, genetics — specifically the ε4 allele(s) of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene3 — and having a family history of AD. Importantly, although age, genetics and family history cannot be changed, there are other risk factors that can be modified to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and AD dementia.

Although age, genetics, and family history cannot be changed, there are other risk factors that can be modified to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and AD dementia.

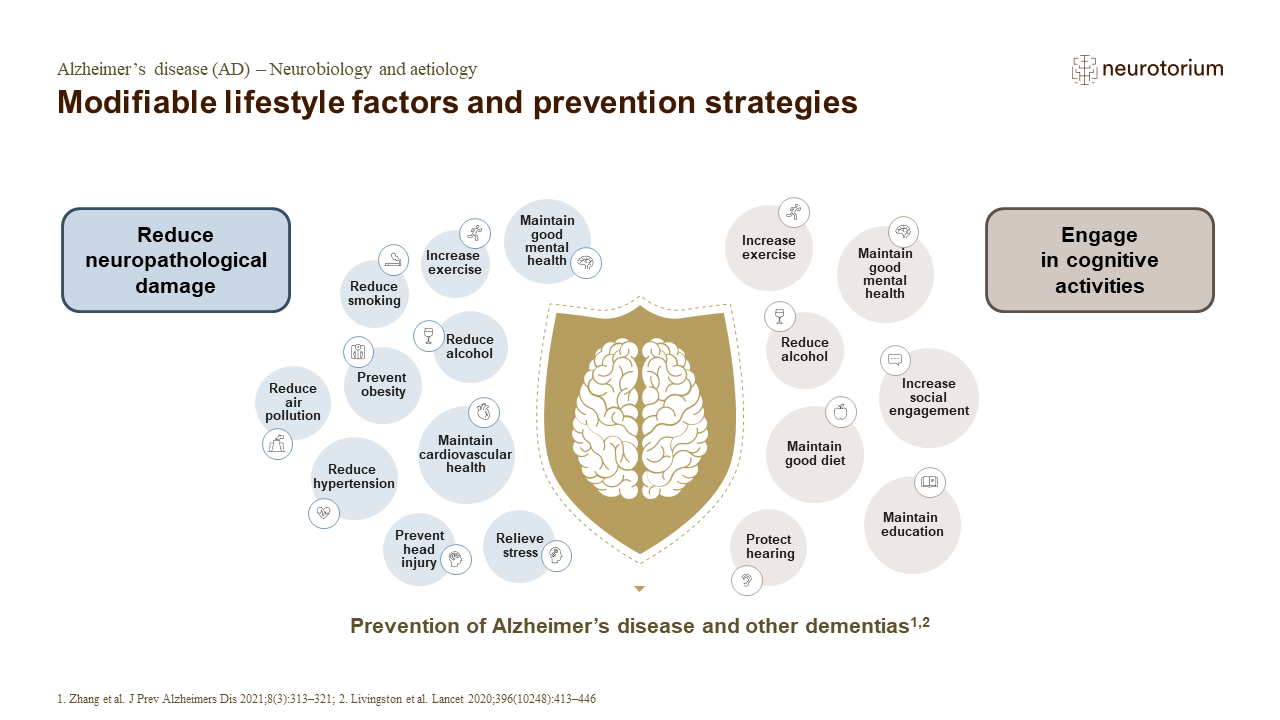

The modifiable risk factors include low educational attainment, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, low social contact, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. In fact, the 2020 recommendations of The Lancet Commission suggest that addressing these modifiable risk factors might prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases.4 In line with this, a study published in 2022 found that nearly 37% of cases of AD and other dementias in the United States were associated with eight modifiable risk factors.5 Modifiable risk factors for AD encompass various stages of life, and several risk factors that become prominent later in life are influenced, to varying degrees, by factors present in middle age and earlier in life. These risk factors can be modified through individual choices, policy interventions, or a combination of both.4 In this article, we will focus on some of the modifiable risk factors for dementia that align with recommendations from prominent sources such as The Lancet Commission, the WHO and the Alzheimer’s Association.

Modifiable risk factors might prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases.4

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health

The health of the heart and blood vessels plays a pivotal role in brain health. A healthy heart ensures an adequate supply of blood to the brain, while healthy blood vessels facilitate the delivery of oxygen and essential nutrients to reach the brain so it can function normally. In a population-based cohort study of persons aged 65 years or older, the researchers found that a higher cardiovascular health score was associated with a lower risk of dementia and lower rates of cognitive decline.6 In contrast, cerebrovascular events, such as stroke, and other factors that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, including midlife obesity, (pre)hypertension and high cholesterol, are indicated to be associated with a higher risk of dementia.6,7 In a study involving over 22,000 individuals spanning the ages of 18 to 89, the research revealed that the cognitive performance of individuals between the ages of 40 to 79 who exhibited none of the eight modifiable risk factors closely resembled that of individuals who were 10 to 20 years younger but had multiple risk factors. This compelling observation underscores the significant impact of modifiable risk factors on cognitive performance and suggests that these factors can magnify the age-related differences in cognitive abilities, potentially accelerating cognitive decline.8 On the other hand, it has been well-established that type 2 diabetes increases the risk for strokes and cardiovascular disease. More recent studies have also identified links between diabetes and dementia. In a longitudinal cohort study of more than 10,000 participants, younger age at onset of type 2 diabetes was significantly associated with higher risk for incident dementia; at age 70, the hazard ratio for every 5-year earlier age at type 2 diabetes onset was 1.24.9 Furthermore, another study has provided evidence that diabetes is related to an accelerated progression of cognitive deterioration, especially when presented with its cardiovascular complications.10

In a population-based cohort study of persons aged 65 years or older, the researchers found that a higher cardiovascular health score was associated with a lower risk of dementia and lower rates of cognitive decline.6

Physical Activity, Smoking, and Diet

Expanding on the connection identified between heart health and brain health, researchers have unearthed compelling evidence that behaviours impacting heart health may also exert a significant influence on the brain, consequently affecting the risk of developing dementia. For example, engaging in physical activity appears to decrease the risk of developing dementia and should be encouraged.11,12 While a wide array of physical activities have been investigated, determining the specific types, frequency, and duration that are most effective in mitigating this risk remains an area of ongoing research.13 Besides participation in physical activities, recent evidence also suggests that adhering to a heart-healthy diet may reduce the risk of dementia.14 Notable examples of heart-healthy diets include the Mediterranean, DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), and MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diets, which all emphasize the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, chicken, nuts, and healthy fats such as olive oil. Simultaneously, it also limits the uptake of saturated fats, red meat, and sugars. These dietary patterns have demonstrated potential benefits for heart health and are associated with a reduced risk of dementia.15 In contrast, the literature has indicated that former/active smoking is related to a significantly increased risk for AD.16 In fact, it has been suggested that 13.9% and 12.7% of AD cases worldwide are potentially attributed to smoking and physical inactivity.17 Therefore, it’s important to note the importance of holistic lifestyle factors in the prevention of dementia.

Engaging in physical activity appears to decrease the risk of developing dementia and should be encouraged.11,12

Education

Education represents one of the most important early life modifiable risk factors for dementia. Higher childhood education levels and higher lifelong educational attainment have consistently been found to reduce dementia risk.18-20 Research from The Lancet Commission reported that 7% of worldwide dementia cases could be prevented by increasing early-life education.4 While lifetime intellectual enrichment (high education, high midlife cognitive activity) is associated with lower Aβ in APOE ε4 carriers, the effects on AD biomarker trajectories (specifically rates) were found minimal. Recent research suggests that rather than reducing the risk of developing AD-related brain changes, education may help sustain cognitive function in mid and late life and delay the development of symptoms.22 Indeed, some researchers proposed that accumulating more years of education builds “cognitive reserve”, which refers to the brain’s ability to make flexible and efficient use of cognitive networks. In essence, cognitive reserve enables individuals to maintain their cognitive abilities and perform cognitive tasks, even when the brain faces challenges or changes associated with aging or dementia.23 In one longitudinal study of cognitively impaired individuals with underlying AD neuropathological changes, the researchers identified education level as the most robust determinant of both cognitive and brain resilience against tau pathology. Findings from that study suggest that high education attainment may be protective against cognitive decline and brain atrophy at lower levels of tau pathology, with a potential depletion of resilience resources with advancing pathology.24

The number of years of formal education is not the only determinant of cognitive reserve. Having a mentally stimulating job and engaging in other mentally stimulating activities may also help build cognitive reserve.25

Some researchers proposed that accumulating more years of education builds “cognitive reserve”, which enables individuals to maintain their cognitive abilities and perform cognitive tasks, even when the brain faces challenges or changes associated with aging or dementia.23

Other Risk Factors

In addition to the low education, the 2023 World Alzheimer Report26 also emphasizes the impacts of socioeconomic status (SES) on dementia risks. It might at first sound surprising, but AD and dementia are not only health issues but also social justice issues. Certain groups of people are not entitled to the same opportunities for education, the same salary, access to health insurance, or the ability to live in high-resourced neighbourhoods with quality healthcare. This social deprivation and inequity contribute to the risk factors that we discussed, and why we see them in marginalized groups as well as the LGBTQ+ community. As there is a combination of factors that underscores the complex and multifaceted relationship between SES and dementia risk, acknowledging these socio-economic inequities is critical for understanding their impacts on the risk of developing dementia. Researchers are actively investigating other potentially modifiable factors that could increase the risk of Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia. While the strength of the evidence for these risk factors may not yet match that of the previously described factors, the body of research is steadily growing. One such factor under scrutiny is the exposure to environmental toxins, particularly air pollution, and its potential link to dementia risk.27,28 The most consistent and rigorous results concern fine particulate matter air pollution resulting from fuel combustion, fires, and dust-producing processes, which has consistently been linked to cognitive decline and dementia incidence.29,30 Another area of growing concern is inadequate or poor-quality sleep.31,32 Studies have indicated that a crucial function of sleep involves the clearance of Aβ and other harmful substances from the brain.33 Poor sleep quality may increase dementia risk by interfering with blood flow to the brain and disrupting normal brain activity patterns essential for memory and attention. Additionally, with the COVID-19 pandemic, emerging research effort has also shed light on how critical illnesses and medical events like hospitalizations among older individuals may increase the risk of long-term cognitive impairment. A substantial number of hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic might potentially contribute to an increased incidence of cognitive impairment.34-36

One such factor under scrutiny is the exposure to environmental toxins, particularly air pollution.27,28 The most rigorous results concern fine particulate matter air pollution resulting from fuel combustion, fires, and dust-producing processes, which has consistently been linked to cognitive decline and dementia incidence.29,30

Final Thought

In the absence of a cure or a treatment that is globally accessible, risk reduction remains the most feasible and proactive way to combat dementia. Managing dementia risk is a multifaceted approach that combines personal choices, community support, and public health efforts. While in reality, some of the most important risk factors for dementia (society, environment, and genetics) are not modifiable by an individual on their own despite their best efforts, there are still many meaningful actions individuals can take to reduce their overall risk and potentially delay the onset of dementia. Eat healthy food, exercise regularly, keep learning and challenging your brain, pay attention to your cardiovascular health and any other chronic diseases, maintain social connections, get enough sleep, and don’t smoke or drink excessive amounts of alcohol. Risk reduction is a lifelong endeavour and is most effective when awareness and understanding of brain health begins at a young age. It is important for individuals to recognize the significant impact of these modifiable risk factors and establish good habits. It is equally essential for researchers to continue identifying other modifiable risk factors and understand how these risk factors may vary across the lifespan and among different racial and ethnic groups, as this knowledge will aid in developing effective strategies for dementia prevention and intervention.

While in reality, some of the most important risk factors for dementia (society, environment, and genetics) are not modifiable by an individual on their own despite their best efforts, there are still many meaningful actions individuals can take to reduce their overall risk and potentially delay the onset of dementia.