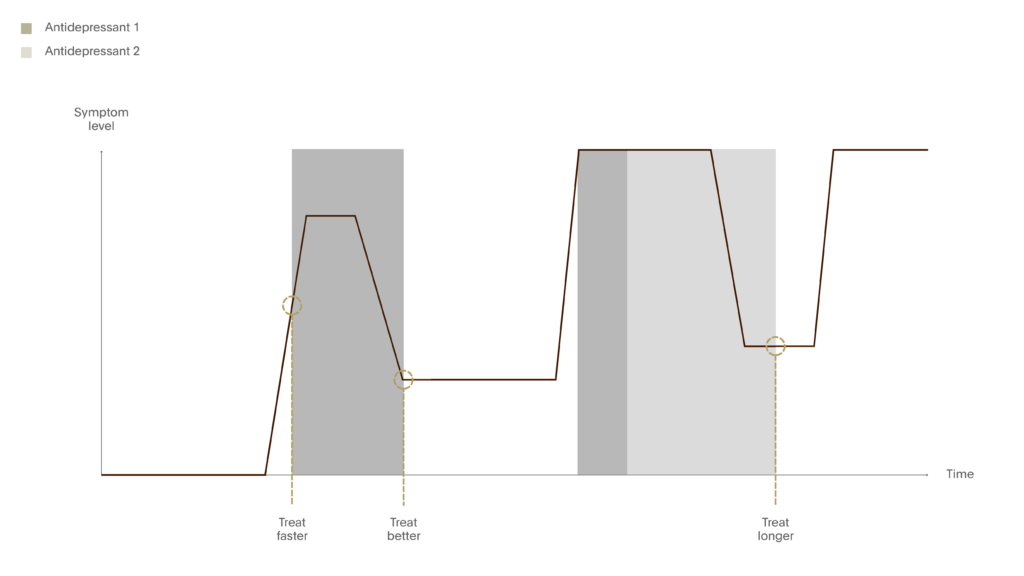

To improve the long-term prognosis of a major depressive episode, clinicians should aim to:

- Treat faster – reduce the duration of untreated illness

- Treat better – focus on the quality remission without tolerating partial response

- Treat longer – prevent relapse and recurrence

Treat Faster

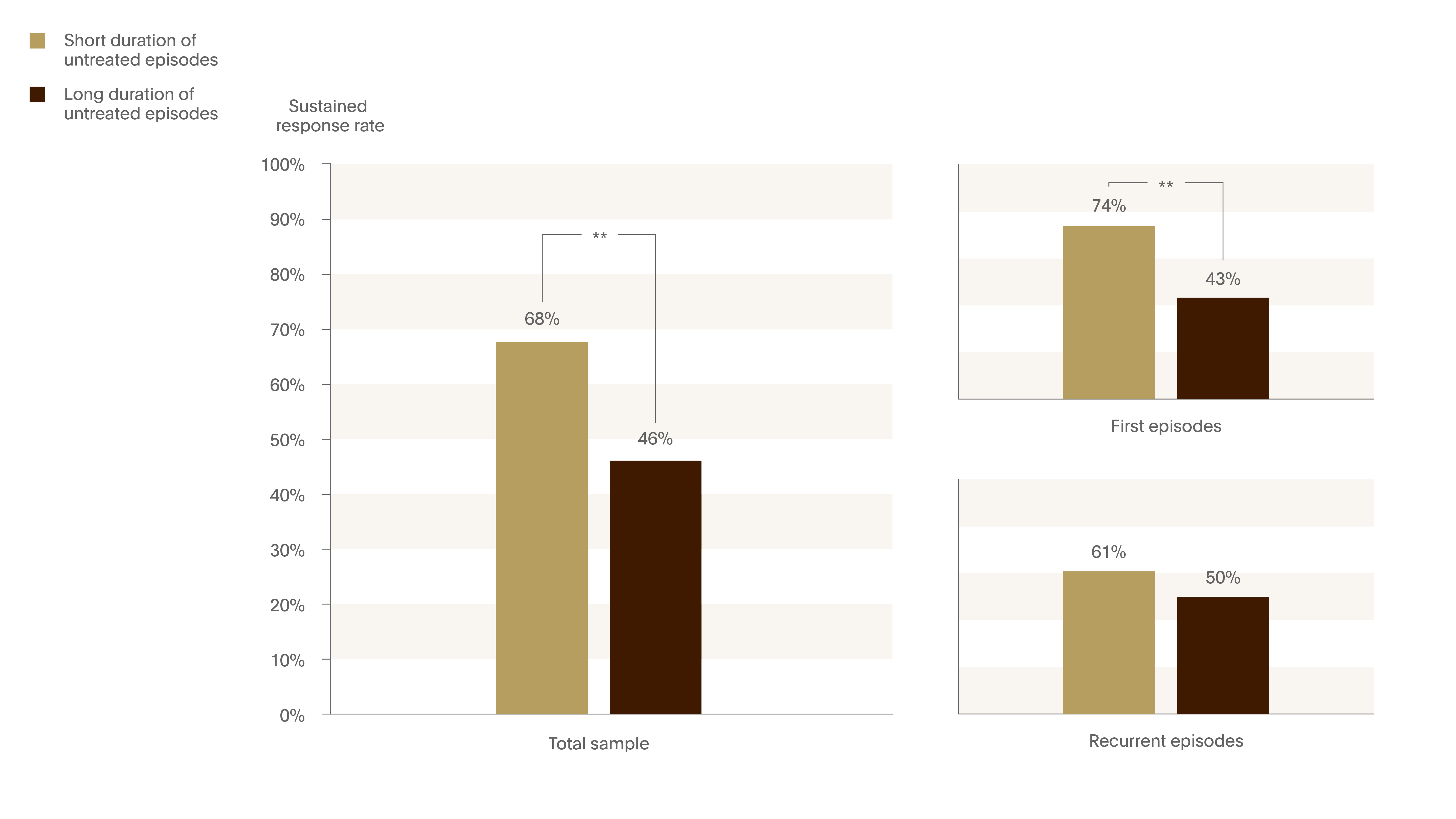

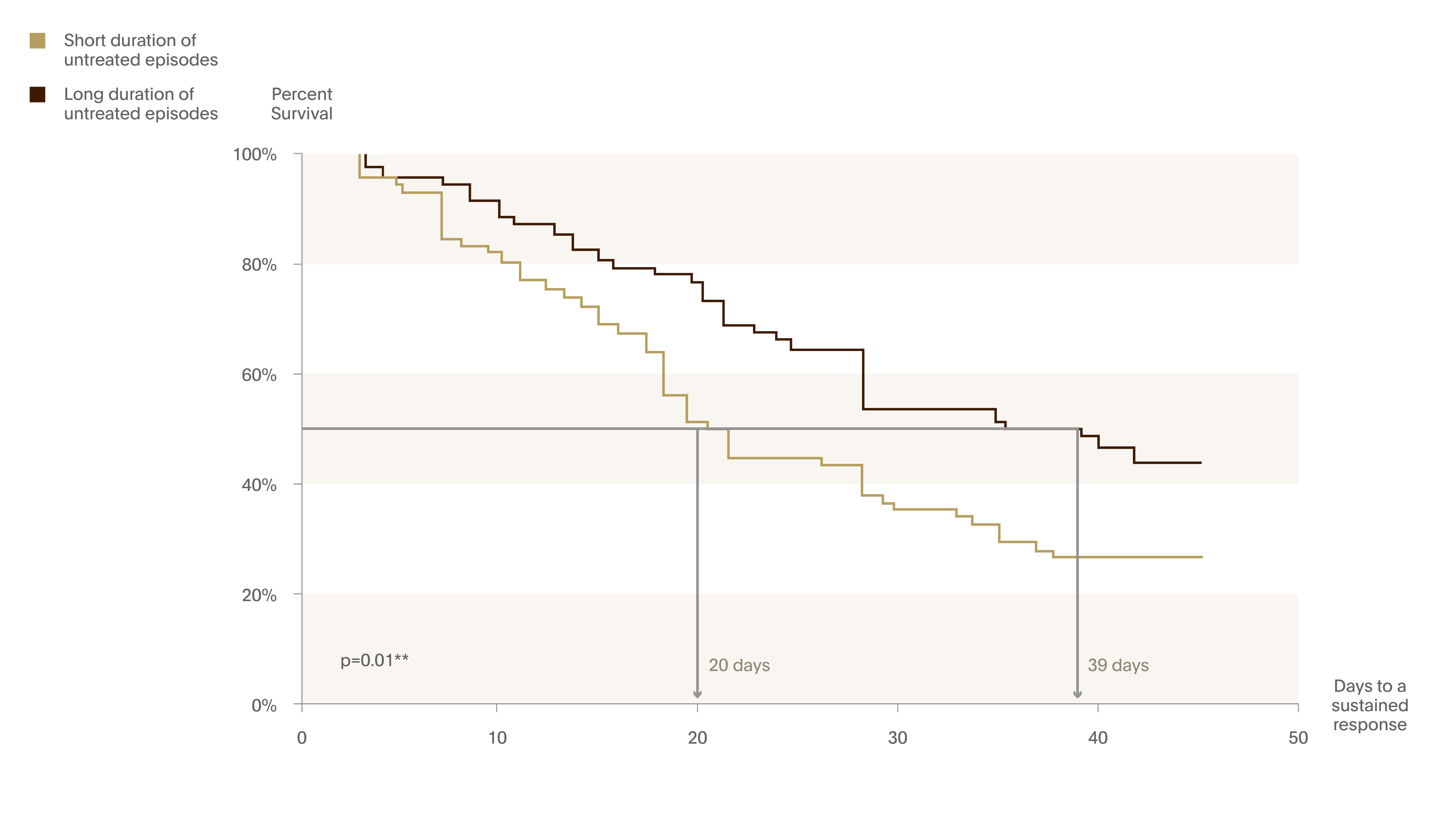

In a seminal study, de Diego-Adeliño and colleagues concluded that early treatment of first-depressive episodes is important since better response is achieved with a shorter duration of untreated illness.1 They looked at the effect of the duration of untreated episode (DUE) on the rate of treatment response, time to attain a sustained response and rate of MDD remission. 141 patients with MDD were grouped into long and short DUE, with long DUE defined as more than 8 weeks. A greater percentage of patients with a short DUE achieved a sustained response [OR=2.6; 95% CI 1.3-5.1], and these patients attained a sustained response more quickly than long DUE patients [39 versus 20 days, p=0.012].

Figure 2. Sustained response rate decrease with longer duration of untreated illness

The effect of the duration of untreated episode (DUE) on rates of response to treatment. MDD patients (n=141) were grouped into long DUE (>8 weeks) and short DUE.

The percentage of patients who achieved a sustained response was significantly higher in the short DUE group (OR=2.6; 95% CI 1.3-5.1). 1

** p<0.01

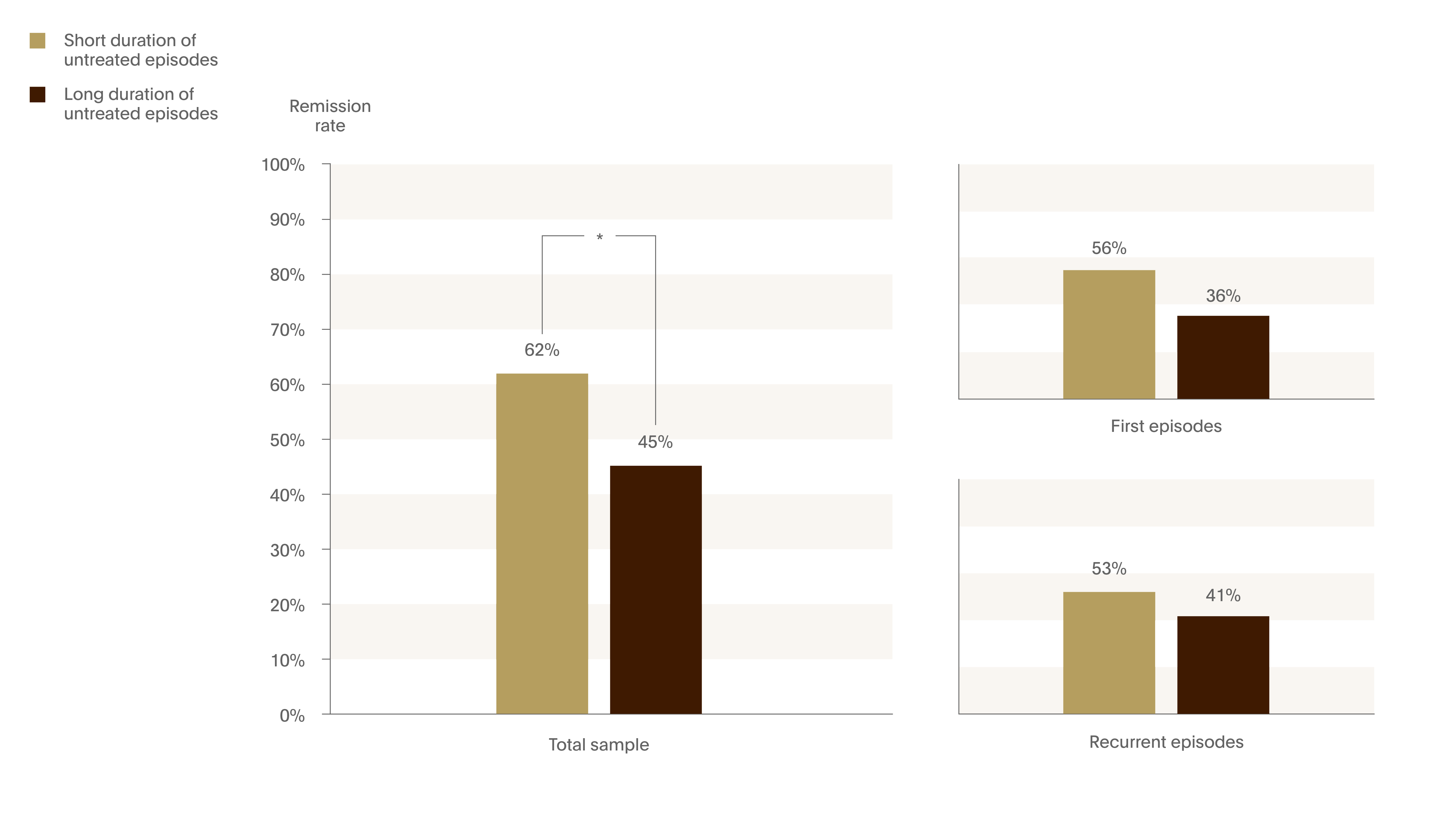

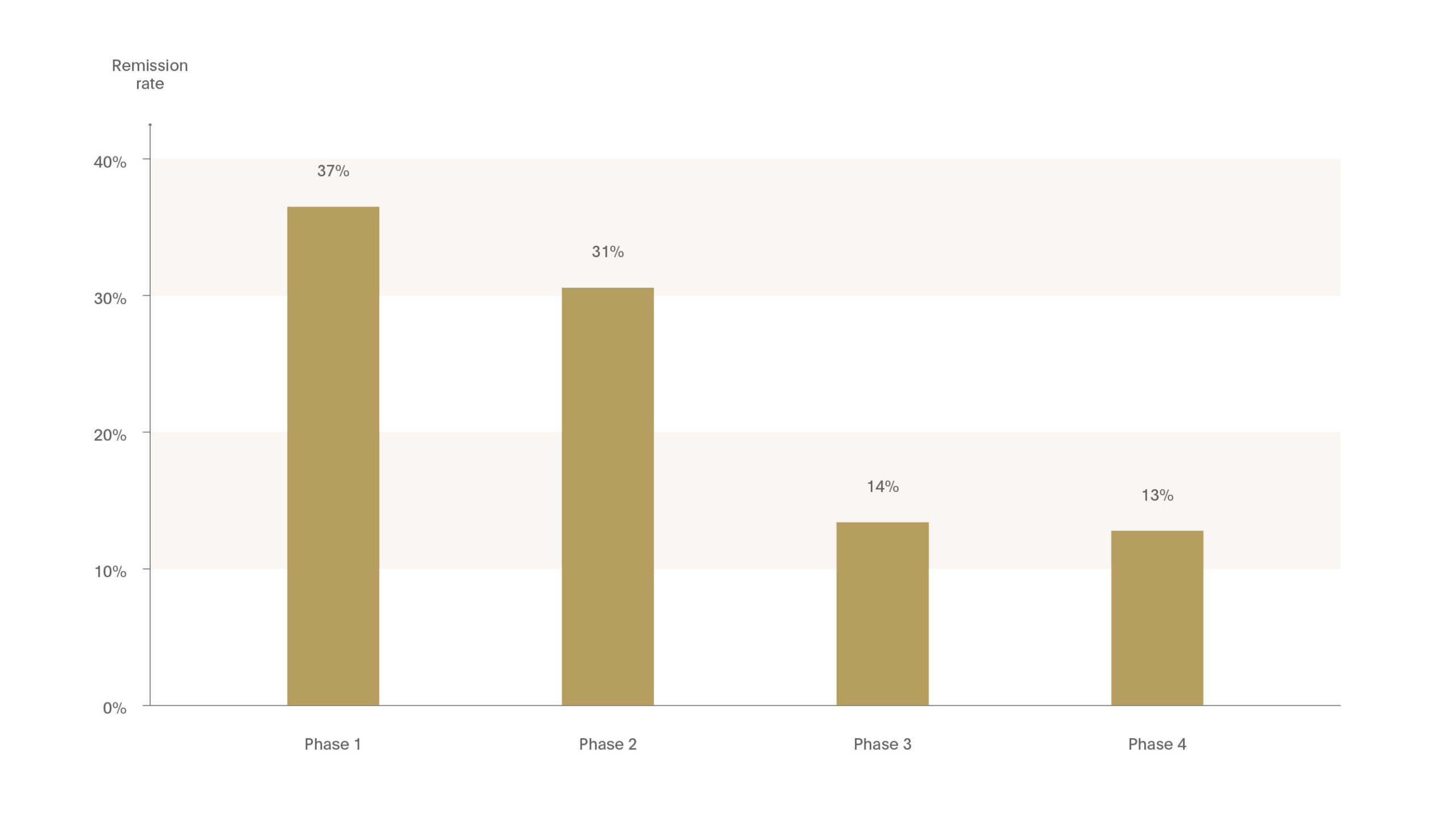

Figure 3. Remission rate decreases with longer duration of untreated illness

The patients with a shorter DUE exhibited higher rates of remission (OR=1.9; 95% CI 1.1-3.9).1

- p<0.05

Figure 4. Survival curves comparing short and long DUE on attaining sustained response

Based on the Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis.

Long DUE group too significantly longer to respond to antidepressant treatment (39 days) than the short DUE group (20 days).1

A long-term study of 94 patients with MDD reported that the duration of depression before recovery predicted the amount of time the patient would be free from symptoms over the next 10 years.2

Don’t wait and see – lost chances

Gorwood highlighted a study that suggests that the approach of ‘wait and see’ does not benefit patients. The investigators plotted the mean Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) scores over time by early and later remission. Both groups achieved remission by the end of the study, but the quality of remission was different. Early remission was associated with rapid functional recovery, and these patients had a 10 point higher SOFAS score at 12 months. The difference in the SOFAS scores between the early and later remission groups represents a ‘lost chance’ of full recovery that means a lot to patients. Patients want to feel that they are as ‘good’ as they were before.3

Treat Better

The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study used a series of treatment trials over up to four treatment steps to define the tolerability and effectiveness of various options in both acute and longer term treatment.4 Remission rates decreased with each step – from 37% in Phase 1 to 13% in Phase 4 treatment. This study demonstrates the importance of maximising the efficacy of first-line treatment to improve the chance of achieving remission.

Figure 5. Chances of remission decreases with each treatment step

The importance of maximising the efficacy of first line treatment to improve the chance of acheiving remission.

The STAR*D study used a series of treatment trials over up to 4 treatment steps to define tolerability & effectiveness of various options in both acute and longer-term treatment. Remission rates decreased with each step (Phase 1:37%, Phase 4: 13%).4

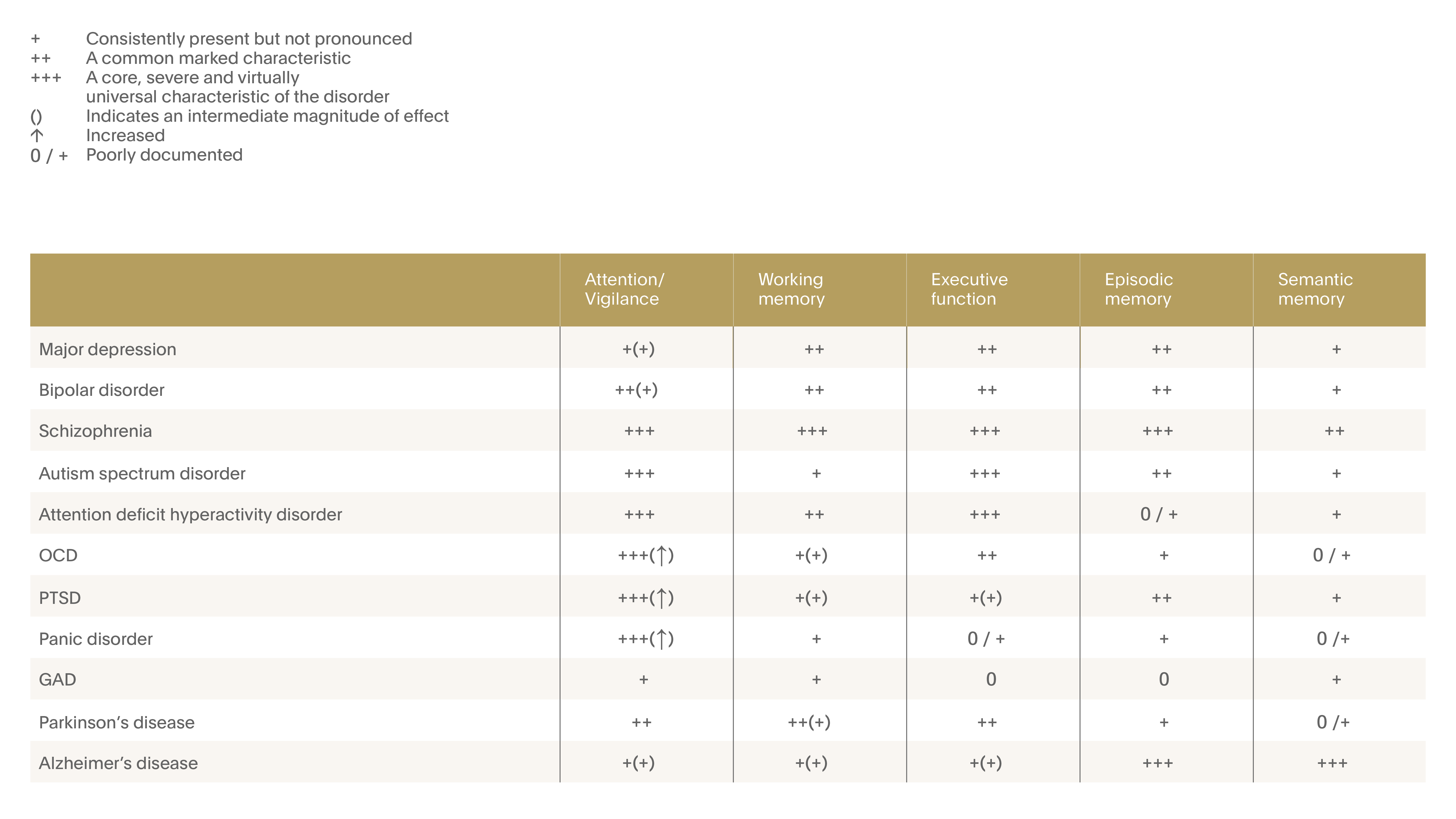

Cognitive consequences

Depression is associated with several cognitive deficits including impaired working memory, executive function, episodic memory and processing speed.

Figure 6. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder (MDD)

Neuropsychological dysfunction in MDD spanning many cognitive domains. Effects on memory and executive function are particularly well documented. 12

Neurotoxicity of Major Depressive Episode (MDE) – Cognitive Consequences

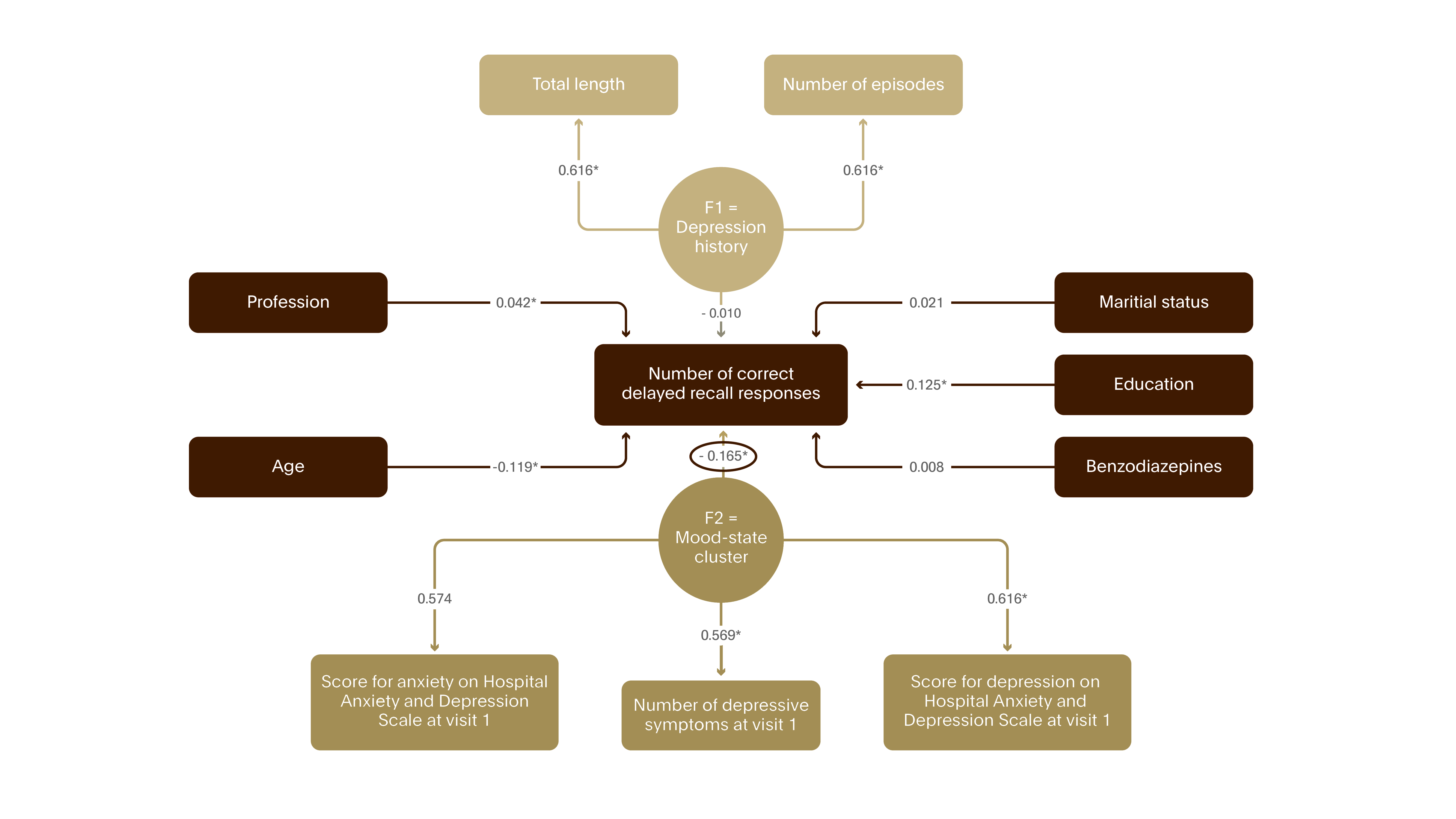

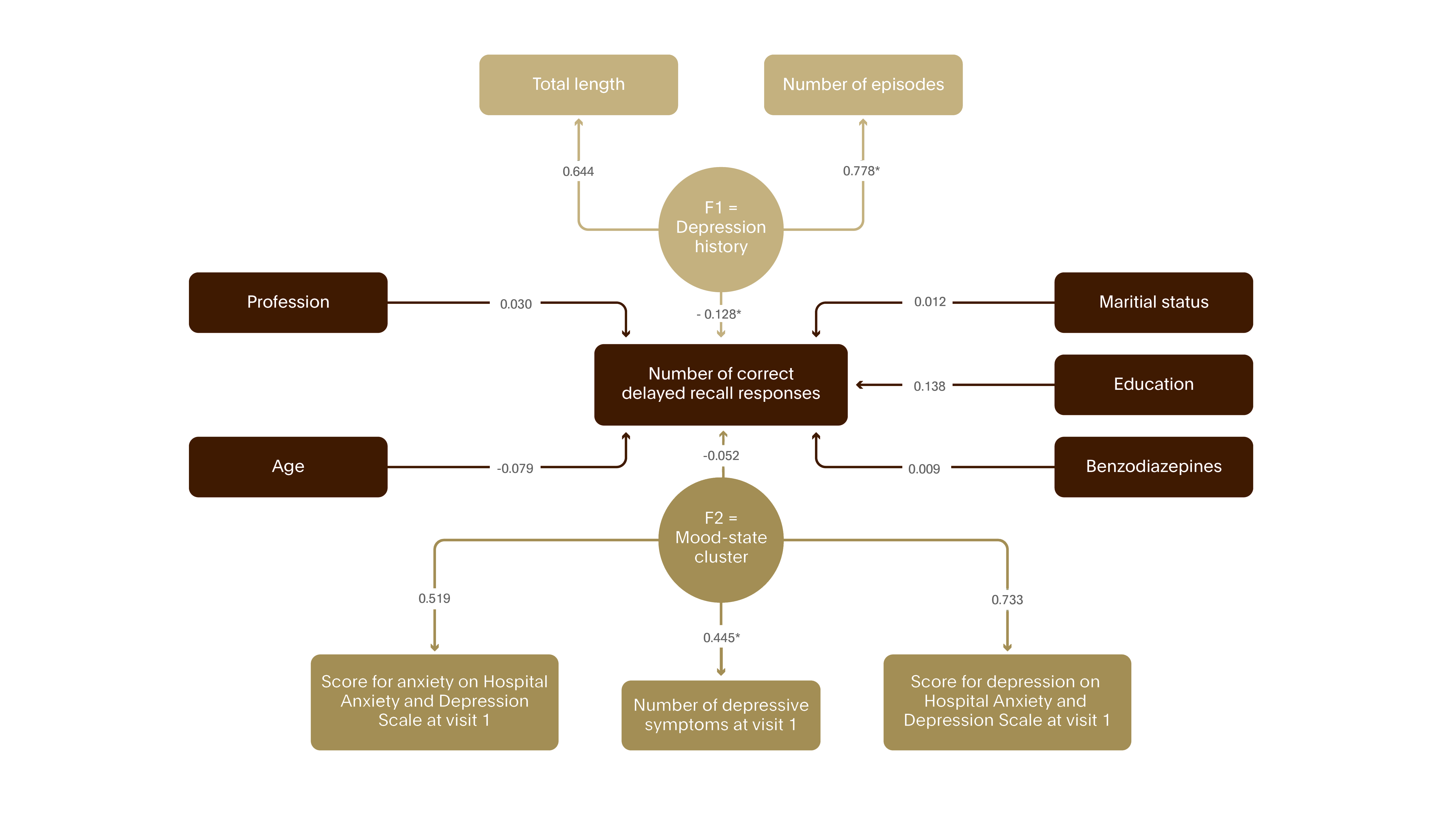

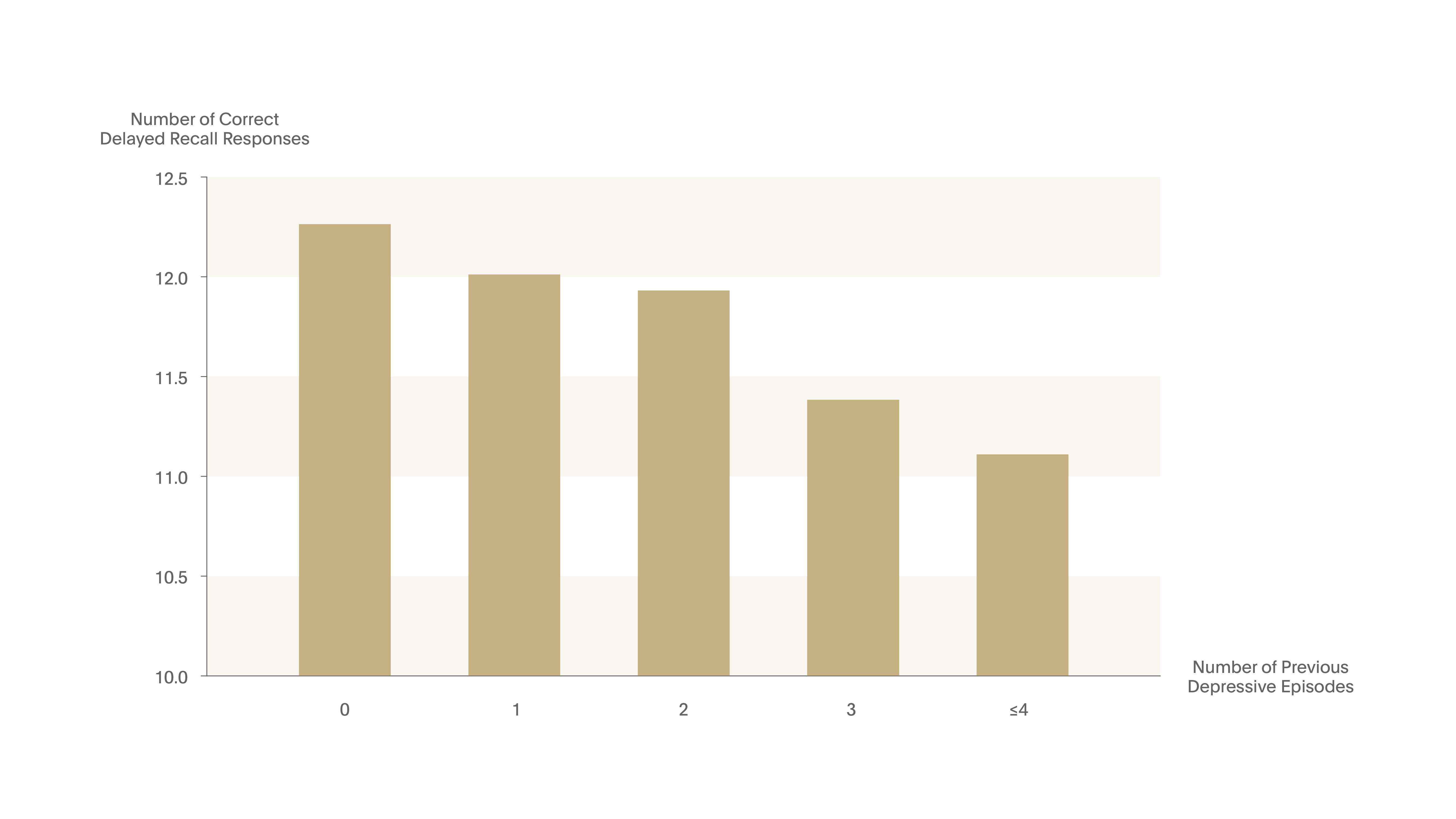

A study of more than eight thousand outpatients suggests that capacity for delayed recall declines steadily with the number of previous depressive episodes.5 Among 1800 depressed patients in remission, who had responded within 6 weeks, the number of recalled words was related to the number of previous episodes. Delayed recall capacities fell by 2-3% for each prior episode.

Figure 7. Neurotoxicity of MDE – cognitive consequences I

The study assessed the impact of depression on hippocampal function. During two visits, several weeks apart 8,229 MDD outpatients were tested for delayed recall, a memory function related to hippocampal integrity. At present, the mood-state cluster (illness severity) was the major determinant of performance as opposed to the depression history cluster (intensity of depressive history).5

Figure 8. Neurotoxicity of MDE – cognitive consequences II

While in remission, after 6 weeks of successful antidepressant treatment, the mood state cluster was much less important than past depression history on the number of recalled words by 1800 depressed patients.5

Figure 9. Neurotoxicity of MDE – cognitive consequences III

Each new episode in outpatients with depression, diminished delayed recall capacities by 2-3%.5

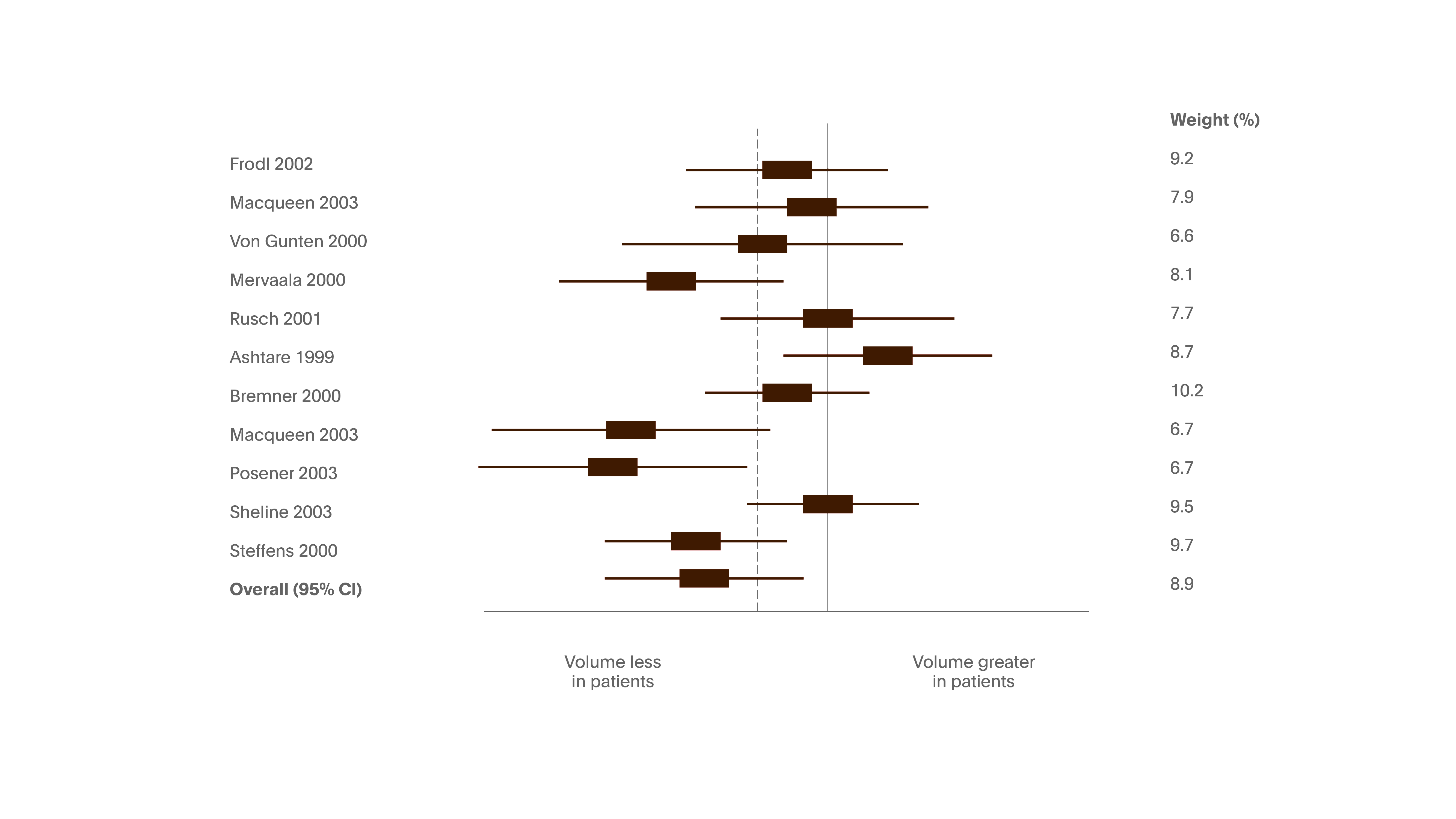

Neurobiological relevance

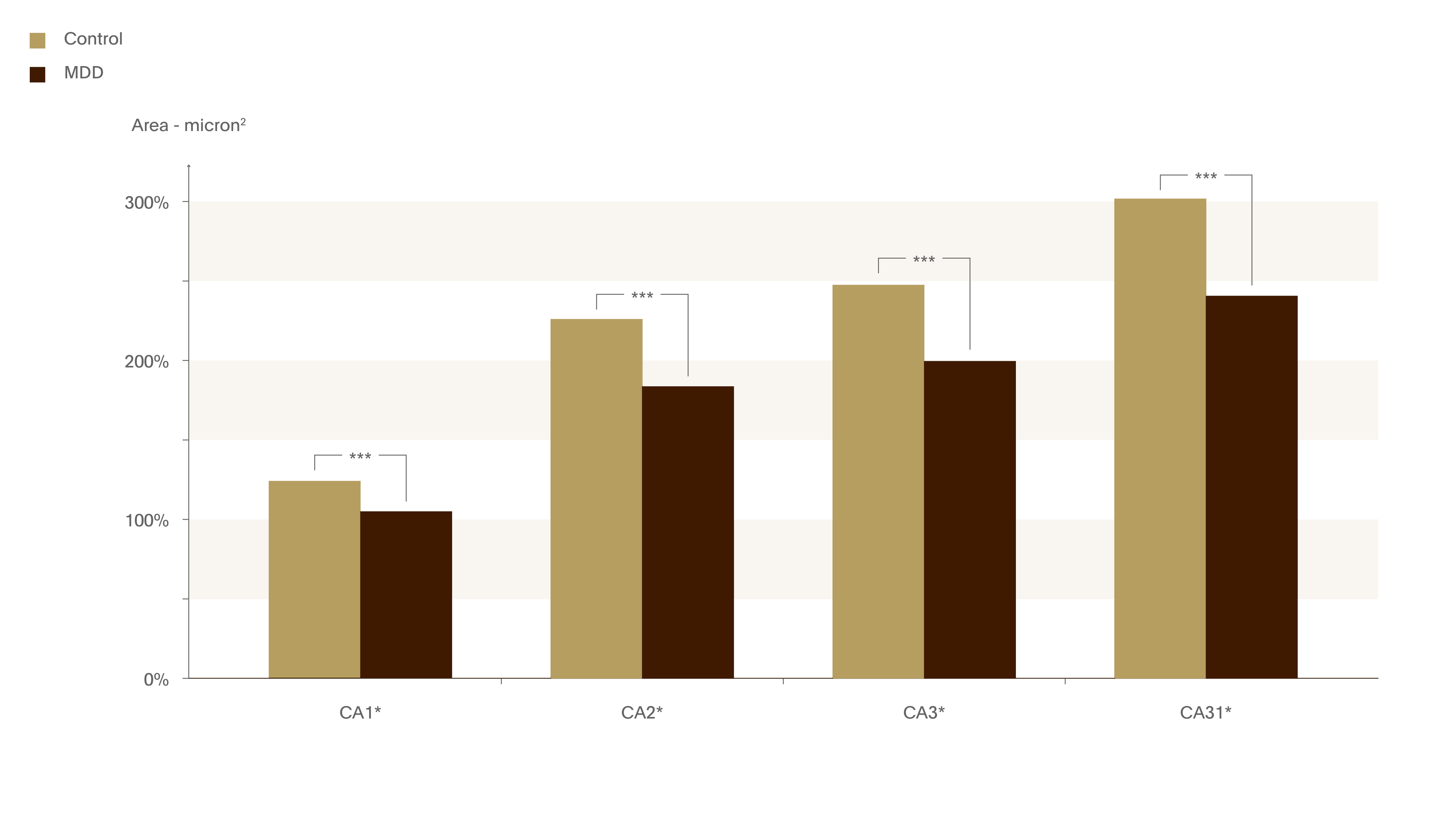

A meta-analysis of 12 studies concluded that depressed patients have a smaller hippocampus than healthy controls, and this may be due to repeated periods of major depressive disorder.6 Stockmeier and colleagues reported cellular changes in the postmortem hippocampus in major depression.7 In subjects with MDD (n=19), hippocampal sections collected at postmortem were shrunk in depth a significant 18% more than in control subjects (n=21).

Figure 10. Left hippocampal volume in patients with depression relative to comparison subjects

In a meta-analysis of 12 studies of unipolar depression, comprised 351 patients and 279 healthy subjects. Participants were heterogeneous regarding age, gender distribution, age at onset of disorder, average number of episodes and responsiveness to treatment. Weighted average: reduction of hippocampal volume by 8% on left side and 10% on the right side. The number of depressive episodes was statistically significantly correlated with right but not the left hippocampal volume reduction.6

Figure 11. Hippocampus in depressed patients.

Few studies have examined the structure of the post-mortem human hippocampus in depression. In this study, sections of right hippocampus were collected from 19 MDD patients and 21 control subjects. Hippocampal sections shrunk in depth a significant 18% more than in control subjects.7

*** p<0.001

Sheline and colleagues reported a link between depression duration and loss of hippocampal volume.8 MRI was carried out on 24 women with a history of recurrent major depression and 24 case-matched controls. Subjects with a history of depression had smaller hippocampal volumes than controls, and there was a significant correlation between hippocampal volume and total lifetime duration of depression.

In a longitudinal study, Frodl et al used MRI to compare the brains of patients with major depression (n=38) with those of healthy control subjects (n=30).9 Compared with controls, patients had a significant decline in grey matter density in the hippocampus, left amygdala, anterior cingulum, and right dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. Interestingly, they also observed this decline in grey matter density in nonremitted versus remitted patients, suggesting that brain decline can be stopped. This highlights the urgency to treat early and effectively to achieve remission.

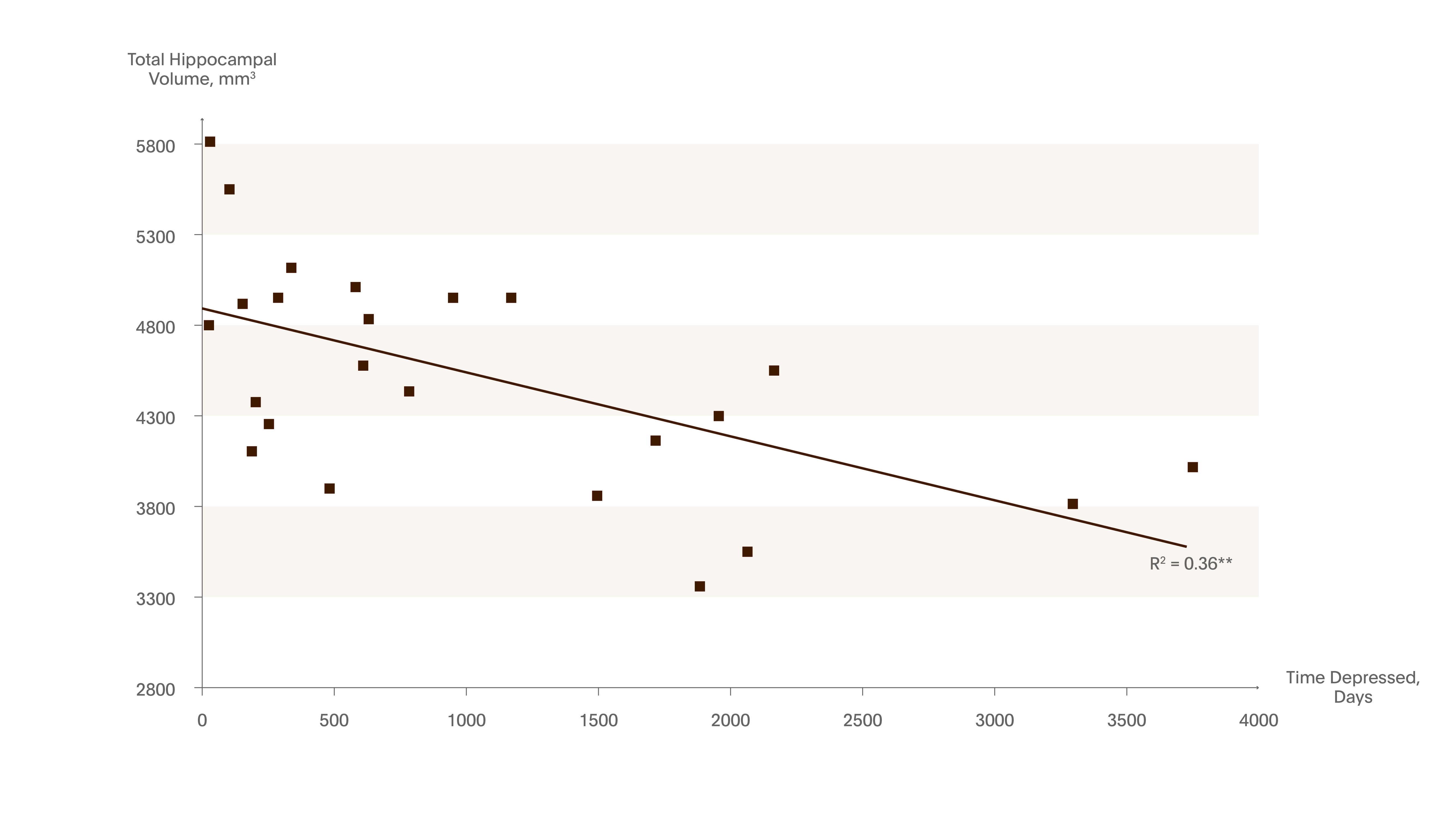

Figure 12. Hippocampal volume decreases with the number of days being depressed

Using MRI, the cumulative duration of depression was inversely correlated with hippocampal volume. The study included 24 women (23-86 years) with a history of recurrent MDD and 24 healthy controls.

Post-depressive patients had:

- Smaller hippocampal volumes than controls

- Scored lower in verbal memory (a neuropsychological measure of hippocampal function)

Suggesting that volume loss was related to an aspect of cognitive functioning. The repeated stress during recurrent depressive episodes may result in cumulative hippocampal injury.8

** p<0.01

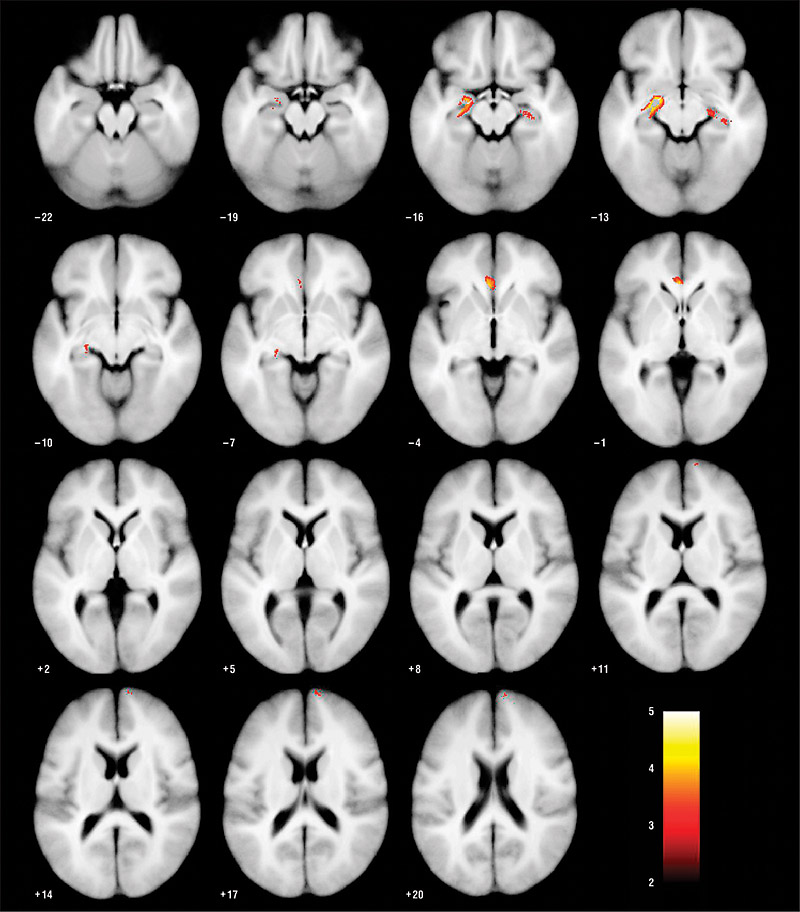

Figure 13. Decline in grey matter volume in MDD patients compared with healthy controls

3-year prospective study comparing 38 patients with 30 healthy controls. Significant decline in gray matter density was noted in the hippocampus, left amygdala, ACC, and right dorsomedial PFC in patients versus controls, and in non-remitted versus remitted (left hippocampus, left ACC, left dorsomedial PFC and bilaterally dorsolateral PFC).9

ACC=Anterior cingulate cortex; PFC=Prefrontal cortex.

Image reproduced from reference with permission.

Treat Longer

Increased recurrence rate – acquired vulnerability

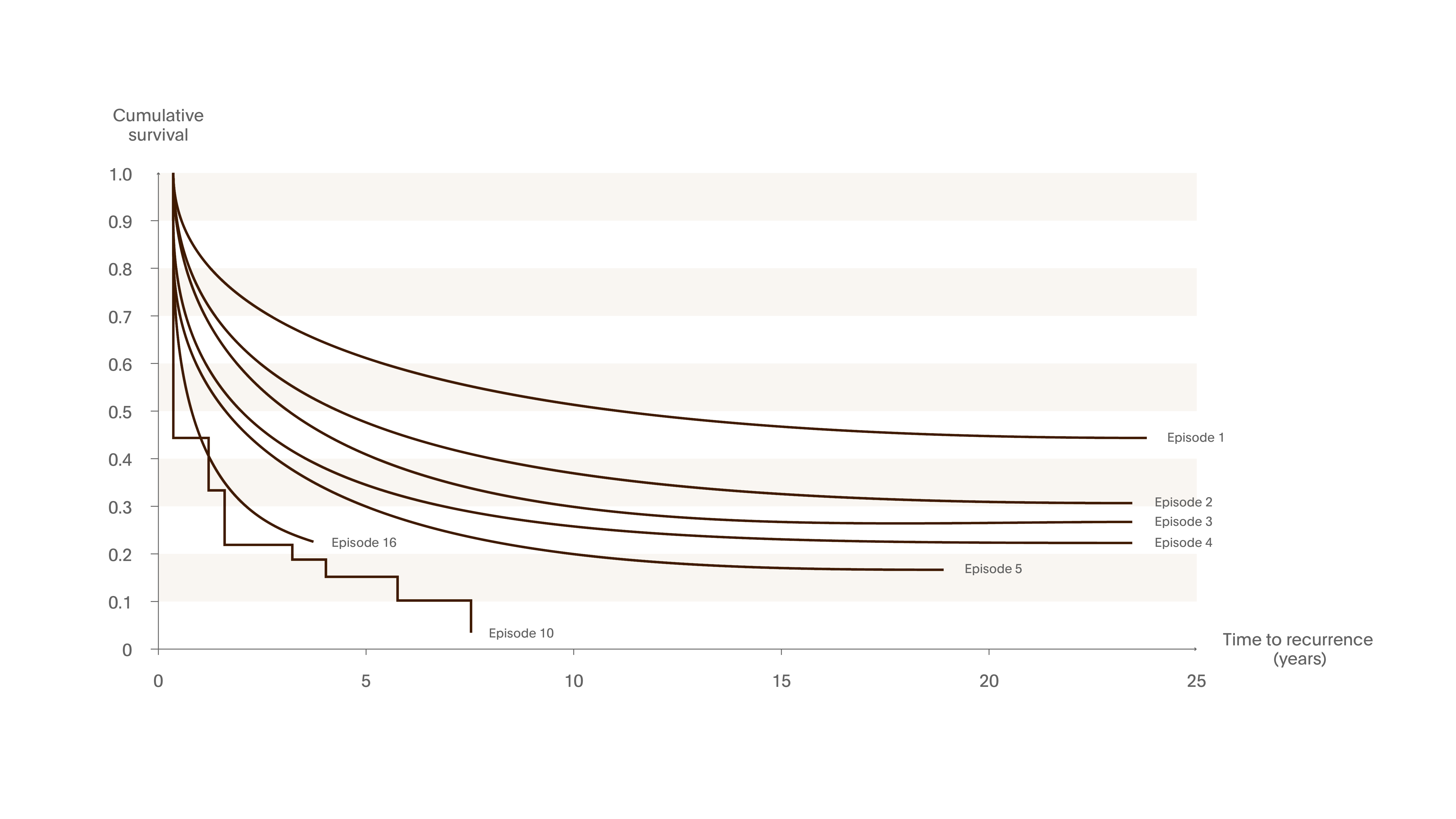

An old study, but the best of its type, looked at 22 years of data on the whole nation of Denmark to understand the rate of depression recurrence.10 This case register study included depressionrelated hospital admissions during 19711993. The rate of recurrence increased with the number of previous episodes – from about 15% with no previous episodes to 60% after 2 previous episodes. After the 10th episode, there was 100% risk of experiencing another recurrence. This study highlights that the course of depression is progressive, and that it is important to prevent relapse and recurrence.

Figure 14. Recurrence worsens with time

In a case register study that included all hospital admissions with primary affective disorder over 22 years over 20,000 first-admission patients were discharged with a diagnosis of affective disorder – depressive or maniac/cyclic type. The rate of recurrence increased with the number of previous episodes.10

Partial remission is the enemy – tell your patients

Don’t let your patient stop treatment if they feel a bit better but have not reached full remission. If they have not returned to their ‘normal self’ – for example if concentration and sleep are still a problem – then treat for longer. Stopping early reduces the chances of full recovery.

Gorwood emphasised the need to share information about the toxicity of depressive episodes with patients. Armed with a better understanding of the importance of treatment for long-term recovery, patients will have the incentive to make their own decision to commit to treatment.

Conclusions: How Could we Prevent the Toxicity of Depressive Episodes?

To improve the long-term prognosis of a major depressive episode, we should:11

- treat faster – reduce the duration of untreated illness

- treat better – focus on the quality of remission, do not tolerate partial response

- treat longer – prevent relapse and recurrence

All images have been redrawn from the reference, unless otherwise stated.

Access article: Depression: Cognitive Function the Next Frontier