Clinical phenotypes of Alzheimer’s disease

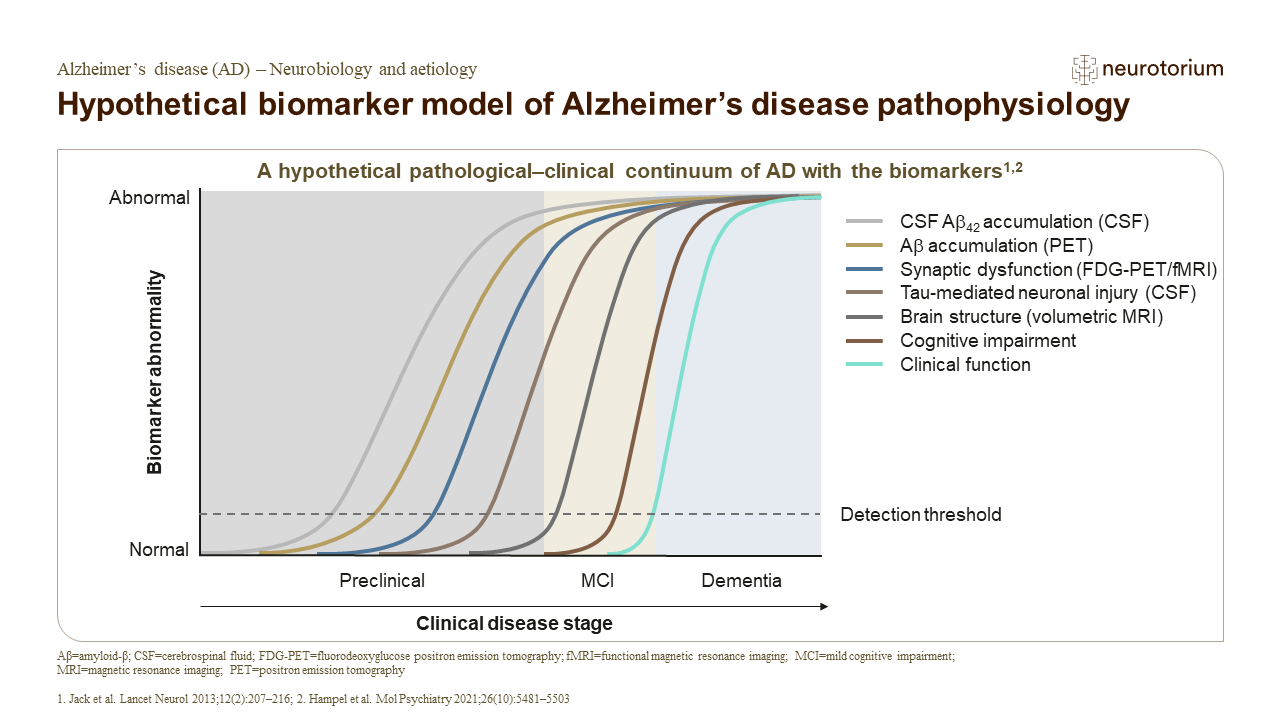

The neuropathology substrate of AD is the brain accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles containing phosphorylated tau protein. These pathological changes lead to neuronal dysfunction and death, and begin 10 to 20 years before the clinical diagnosis.2 The course of the disease includes a preclinical stage, followed by the stages of subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and, ultimately, dementia.3

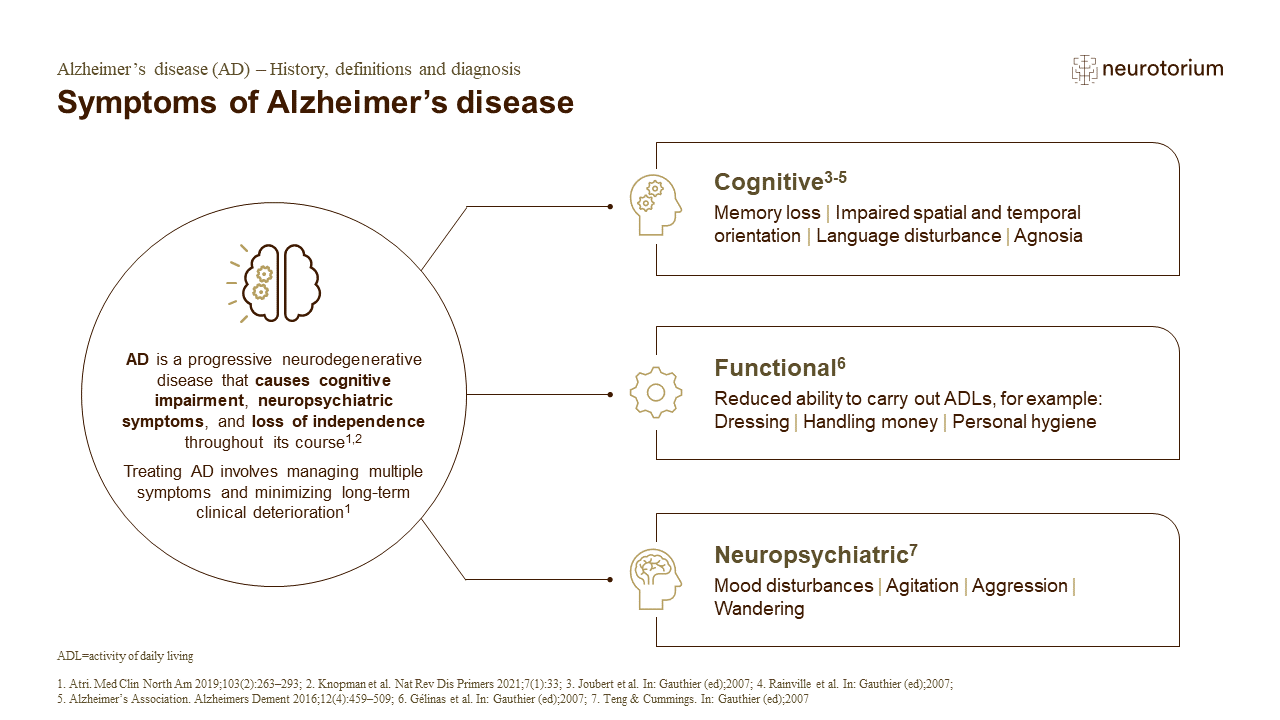

AD is clinically characterized by cognitive decline, being memory impairment the earliest and most prominent symptom in around 85% of the cases.4,5 The remaining cases constitute non-amnestic or atypical variants of AD, with predominance of language symptoms (primary progressive aphasia-logopenic variant), visual symptoms (posterior cortical atrophy), dysexecutive/behavioral symptoms (behavioral/dysexecutive variant), or more prominent motor symptoms (corticobasal syndrome).6 These atypical phenotypes are more common in early-onset cases, i.e., when symptoms emerge before the age of 65 years.7 Behavioral or neuropsychiatric symptoms are also very common over the course of the disease, from apathy (the most frequent behavioral symptom), depression and anxiety, to agitation, aggressiveness, irritability, delusion, wandering, disinhibition and hallucinations.8

Diagnosis and therapeutic management of Alzheimer’s disease

Diagnosis of AD is based on clinical history (with the affected person and a close informant) and structured clinical assessment, which must include cognitive and functional evaluation, physical examination, as well as laboratory tests and structural neuroimaging (e.g., computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MRI) of the brain). These latter two procedures aim to exclude other causes of cognitive impairment, but neuroimaging (especially MRI) can depict atrophy of the medial temporal lobes that serves as a biomarker of neurodegeneration and may be a supportive feature for the diagnosis of AD.5

In recent years, specific biomarkers have emerged as useful diagnostic tools, allowing earlier and more precise diagnosis. AD biomarkers can be classified as amyloid-related (e.g., low levels of beta-amyloid 42 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or increased amyloid deposition in the brain detected by positron emission tomography (PET) images using amyloid radiotracers) or tau-related (e.g., increased levels of phosphorylated tau levels in the CSF or increased tau protein deposition in the brain in PET images using tau radiotracers).6 Biomarkers are especially useful for the diagnosis of AD in the prodromal stage of MCI, for the differentiation with other causes of cognitive impairment (especially other neurodegenerative diseases) and in cases with atypical clinical presentations.9

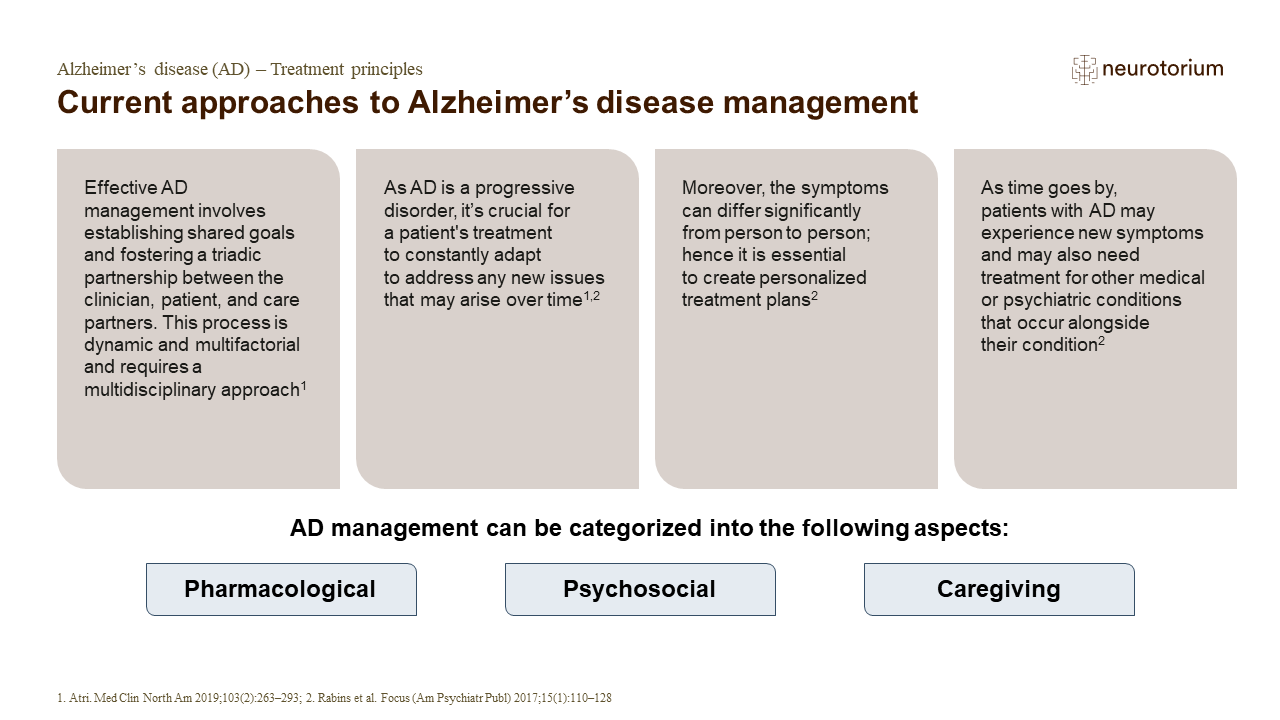

Accurate diagnosis of AD is paramount for proper therapeutic management. Treatment of AD includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine) and memantine have been approved for the treatment of different stages of AD dementia.10 More recently, monoclonal antibodies (aducanumab, donanemab and lecanemab) were approved by some drug federal agencies for the treatment of MCI or mild dementia due to AD, although commercialization of aducanumab has been subsequently discontinued.11,12

Different non-pharmacological treatments have been proved useful for the management of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia due to AD, such as cognitive stimulation therapy, multidisciplinary cognitive rehabilitation, reality orientation, and psychosocial intervention for people with dementia and their caregivers.10

Alzheimer’s disease in low-resource settings: The challenges

Around 2/3 of people with dementia live in low- or middle-income countries (LMIC).13 Different factors impede the timely and accurate diagnosis of AD in these countries, particularly in scenarios with low resources.

One of the primary challenges in resource-limited settings is the lack of awareness and understanding of AD and dementia symptoms by the general population. Stigma, misconceptions, and cultural beliefs can hinder timely diagnosis and access to care. Symptoms of cognitive decline are often considered to be part of normal aging, significantly delaying diagnosis (or leading to non-diagnosis) and intervention. Therefore, community education programs and awareness campaigns tailored to local cultures and languages are essential to increase recognition of the disease and to encourage seeking medical help.

Around 2/3 of people with dementia live in low- or middle-income countries (LMIC).13 Different factors impede the timely and accurate diagnosis of AD in these countries, particularly in scenarios with low resources

Another significant challenge is the scarcity of specialized healthcare professionals trained in Geriatrics, Neurology, or Old Age Psychiatry. Moreover, in many of LMIC countries general practitioners do not receive adequate training in dementia diagnosis and care.14 In rural areas of some LMIC, the nearest physician might be hundreds of kilometers away, causing significant delays in diagnosis and treatment.15

Diagnostic tools such as neuropsychological assessment and neuroimaging (MRI, PET) are often unavailable or too expensive in these settings. Consequently, many cases go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, exacerbating suffering of the affected people and their families, and hindering access to appropriate care and support services.16

Cultural and linguistic diversity adds another layer of complexity to AD diagnosis and management in resource-limited settings. In many regions, traditional beliefs and stigma surrounding mental illness prevail, leading to underreporting and reluctance to seek medical help.13,17 Additionally, language barriers can impede effective communication between affected individuals, family caregivers, and healthcare providers, affecting the accuracy of diagnostic assessments and treatment adherence.16

Diagnostic tools such as neuropsychological assessment and neuroimaging (MRI, PET) are often unavailable or too expensive in these settings. Consequently, many cases go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed

Treating AD poses significant challenges, especially in resource-limited settings where access to pharmacotherapy and supportive care is constrained. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine are costly for people from low socioeconomic levels and are not covered by public health programs in many countries. Consequently, many families must assume the financial burden of treatment.13,14

Treating AD poses significant challenges, especially in resource-limited settings where access to pharmacotherapy and supportive care is constrained

Finally, non-pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive stimulation therapy or caregiver support programs, are scarce in resource-limited settings due to funding constraints and to a shortage of trained health professionals.16 The restricted access to comprehensive care exacerbates the burden on caregivers and diminishes the quality of life for affected people and their families, leading to caregiver depression and burnout, and compromising their physical and mental health.

Alzheimer’s disease in low-resource settings: Possible solutions

The approach to tackle the challenges of AD in resource-limited settings requires a multifaceted strategy that encompasses capacity building, engagement of the community, and public health policies. Investments in training healthcare workers at the primary care level and raising public awareness about AD/dementia are essential steps toward improving diagnosis, treatment, and support.14

Community-based interventions, such as caregiver training programs and care services, are promising in alleviating caregiver burden in resource-limited settings. However, these initiatives require sustainable funding and collaboration between government agencies, non-profit organizations, and local communities to be effective.18

The approach to tackle the challenges of AD in resource-limited settings requires a multifaceted strategy that encompasses capacity building, engagement of the community, and public health policies

Technological advances may help to overcome some of the challenges associated with diagnosis and care of AD and dementia in resource-limited settings. Telehealth applications, for instance, can facilitate remote clinical monitoring and adherence to treatment even in underserved areas. Telemedicine platforms are also promising in improving access to specialized care individuals living in remote regions, such as rural areas. Online consultations by experienced clinicians can be provided, thus reducing the costs and sparing time with travels to distant regions. However, technological solutions must be adapted to the context of the specific settings, considering factors such as internet access, educational level, cultural issues and population acceptance.18

Furthermore, governments and non-profit national and international organizations must consider AD and dementia as a public health priority and allocate adequate resources to community education, research, prevention, diagnosis, and care. Collaborative efforts between governments, non-government organizations, academia, as well as the private sector, are essential to develop sustainable solutions that meet the needs of vulnerable populations affected by AD in low-resource settings. In this sense, creation of national dementia plans in LMIC is essential to deal with the growing impact of AD and related disorders in these countries.20

Collaborative efforts between governments, non-government organizations, academia, as well as the private sector, are essential to develop sustainable solutions that meet the needs of vulnerable populations affected by AD in low-resource settings

Conclusion

AD and dementia pose significant challenges in resource-limited settings, where access to healthcare, diagnostic tools, and treatment options is often limited. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive approach that involves capacity building, community engagement, technological innovation, and public health policies. Investments in education of the general public about AD/dementia symptoms, early diagnosis, comprehensive care, and caregivers’ support are necessary to alleviate the burden of affected people, their families, and healthcare systems, ultimately promoting a more inclusive and equitable approach that may provide better quality of life for these individuals.